#0024 - Aseem Malhotra

We break down the April 2023 interview with Dr Aseem Malhotra.

-

Manchester Evening News | Young doctors hit by 'flawed' NHS system

-

Pulse | NICE rules Alzheimer’s-slowing drug lecanemab too expensive for NHS

-

Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against Hospitalization in the United States, 2019–2020

-

Estimated Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccines in Preventing Secondary Infections in Households

-

COVID-19 Vaccine Benefits Outweigh Small Risks, Contrary to Flawed Claim From U.K. Cardiologist - FactCheck.org

-

Shift to updated COVID vaccine isn’t tied to safety concerns | AP News

-

The Skeptic | How cholesterol denialism went from reasonable skepticism to pseudoscience

-

Cochrane | Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease

-

VOX | How bad reporting on statins may have led thousands to quit their meds

-

JACC Z Side Effect Patterns in a Crossover Trial of Statin, Placebo, and No Treatment

-

Management of Statin Intolerance in 2018: Still More Questions Than Answers

-

Discontinuation of Statins in Routine Care Settings: A Cohort Study

-

Lack of an association or an inverse association between low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality in the elderly: a systematic review (Criticism: https://pubpeer.com/publications/EE6235919FD91A0E9E43C6D2C8910C)

-

NICE | More people are benefitting from NICE-recommended statins to reduce heart attacks and strokes

Clips used under fair use from JRE show #1979

Listen to our other shows:

-

Cecil - Cognitive Dissonance and Citation Needed

-

Marsh - Skeptics with a K and The Skeptic Podcast

Intro Credit - AlexGrohl:

https://www.patreon.com/alexgrohlmusic

Outro Credit - Soulful Jam Tracks: https://www.youtube.com/@soulfuljamtracks

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1 I'm Chandler Garcia. As a PICU nurse and global health advocate, I've cared for women and children all over the world, from Costa Rica to Egypt to Kenya and beyond.

Speaker 1 And no matter where I go or how tough the conditions get, I always wear my FIGs. These scrubs are lightweight, breathable, and super soft, perfect for long shifts in any environment.

Speaker 1 They've got pockets in all the right places, the fit is flexible, and they're durable through every admission, surgery, and post-op. But it's not just about the scrubs.

Speaker 1 Another big part of what I love about Figs is when they say they're committed to supporting healthcare workers all over the world, they mean it.

Speaker 1 I recently joined them on an impact trip to India where I worked in triage, caring for babies in a mobile clinic. My figs aren't just what I wear, they're part of the impact I want to make.

Speaker 1 Wherever my work takes me, Figs helps me show up ready to make a difference while looking and feeling my best. Get 15% off your first order at werefigs.com with code FIGSRX.

Speaker 1 That's wherefigs.com, code FIGSRX.

Speaker 3

AI agents are everywhere, automating tasks and making decisions at machine speed. But agents make mistakes.

Just one rogue agent can do big damage before you even notice.

Speaker 3 Rubrik Agent Cloud is the only platform that helps you monitor agents, set guardrails, and rewind mistakes so you can unleash agents, not risk. Accelerate your AI transformation at rubrik.com.

Speaker 3 That's r-u-b-r-i-k.com.

Speaker 2

On this episode, we cover the Joe Rogan Experience, episode number 1979 with guest Dr. Asim Malhatra.

The No Rogan Experience starts now.

Speaker 2 Welcome back to the show. This is a show where two podcasters with no previous Rogan experience get to know Joe Rogan.

Speaker 2 It's a show for those who are curious about Joe Rogan, his guests, and their claims, as well as for anyone who wants to understand Joe's ever-growing media influence.

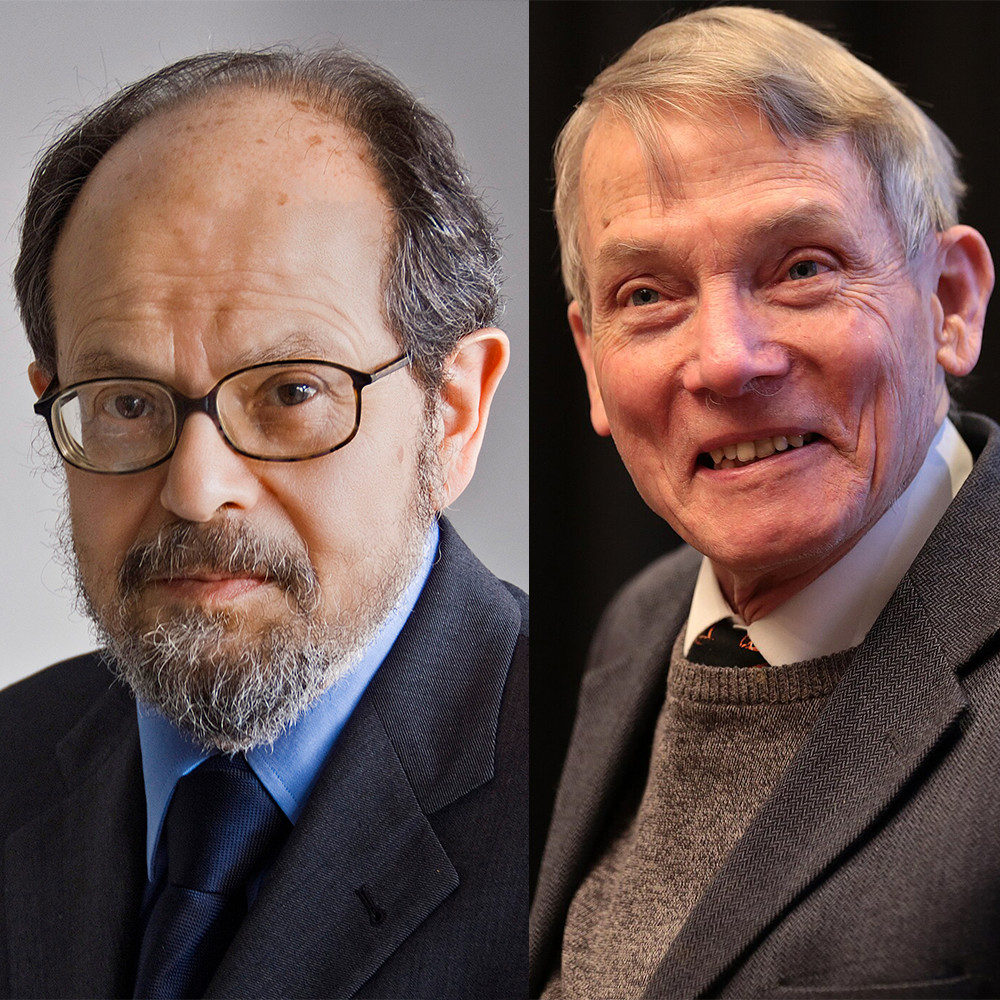

Speaker 2 I'm Cecil Cicerello, joined by Michael Marshall, and today we are going to be covering Joe's April 2023 interview with Dr. Asim Malhatra.

Speaker 2 Marsh, how did Joe introduce Dr. Malhatra in the show notes?

Speaker 4

So, according to the show notes, Dr. C.

Malhotra M.D.

Speaker 4 is an NHS-trained consultant cardiologist and visiting professor of evidence-based medicine at the Bahaina School of Medicine and Public Health in Salvador, Brazil.

Speaker 4 And he is the author of several books, including the Piopi Diet, The 21-Day Immunity Plan, and A Statin-Free Life.

Speaker 2 Okay. Is there anything else we should know about him?

Speaker 4 Yeah, I think there is. So Malhotra is somebody that is relatively well known, certainly in skeptical circles of the UK, someone whose career I've been watching for a while.

Speaker 4 So he made a name for himself as a cardiologist who, as his book title might suggest, advocates very strongly against the use of statins.

Speaker 4 He's described them as a multi-billion dollar con by the pharmaceutical industry. He's accused his critics of receiving millions in research funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Speaker 4 And then in 2017, his other book, The Peopy Diet, in that he claimed that his diet could prevent 20 million deaths per year from cardiovascular disease if they just followed the diet in his book.

Speaker 4 The book was named by the British Dietetic Association as one of the worst celebrity fad diets of the year.

Speaker 4 The whole point of the diet is you eat like this Mediterranean village called Piopi.

Speaker 4 But the British Dietetic Association points out that this apparently Mediterranean diet excluded carbohydrates, which means you couldn't eat pasta or bread, but you could eat coconuts, which arguably isn't very Italian as a diet.

Speaker 4 That you assume carbs, not so much.

Speaker 2 What if they grip it by the husk and they threw it over there?

Speaker 4 That would be, maybe. Yeah.

Speaker 4 And then in 2021, mid-pandemic, he published the book, actually, 2020, I think it was, mid-pandemic, he published the book the 21-day immunity plan, which promoted a diet that he claimed would improve the immune system and help fight off infections like COVID-19, which it couldn't.

Speaker 4 You can't do that with a diet. Then when the vaccine came out, he published a paper that claimed vaccines pose a serious risk to cardiovascular health.

Speaker 4 And he said the vaccines were at best a reckless gamble.

Speaker 4 That paper was published in a peer-reviewed journal, but the journal was the Journal of Insulin Resistance, which might seem a kind of strange place to publish an article from a cardiologist.

Speaker 4 about a vaccine until you learn that Mahotra is involved with the editorial board. So maybe that's why he chose that particular journal.

Speaker 4 His anti-vax campaign in the UK found a very willing audience in member of parliament Andrew Bridgen, who was at the time a member of the Tory party, who is no longer an MP, no longer a member of the Tory party, and now a notorious conspiracy theorist.

Speaker 4 And in my opinion, Malhotra is one of the key figures in radicalizing Andrew Bridgen. Bridgen even cites Malhotra as kind of one of the people who opened his eyes.

Speaker 4

In 2023, the Skeptic magazine, which is the magazine that I edit, we gave Malhotra the Rusty Razor Award for the pseudo-scientist of the year. Wow.

He didn't answer, didn't accept it.

Speaker 4 And since Trump's election, there have been a string of stories across the media, in the UK and internationally, describing Malhotra as a top doctor who is tipped for a role in Trump's health team.

Speaker 4

And when you read pretty much any of those stories, the person that's doing the tipping is Dr. Asim Malhotra.

Essentially, he's got friends in the newspapers that he was seeing these stories.

Speaker 4 And he isn't really considered a top doctor in the UK. In fact, the General Medical Council is currently reviewing whether his actions require a fitness to practice investigation,

Speaker 4 which could end up with him losing his medical license. Nevertheless, on May the 14th of this year, he was named by the NIH director Jay Bhattacharya as the chief medical advisor to the United States.

Speaker 2 Woof. Well, that's why we're talking about him, I guess.

Speaker 4 Very much is.

Speaker 2 Very much it is. This has been a sort of a string of people that have been involved in RFK with Casey and Callie Means and now

Speaker 2 Melhatra who are all part of what's going to be United States health policy, which is, I think, a very important thing to talk about. So what did they talk about on this show?

Speaker 4 They talked about big pharma, corrupt doctors, clinical trials, a lot of clinical trials, in fact.

Speaker 4 They talked about statins, heart attacks, COVID, vaccines, side effects, and how all of the coolest and smartest and most qualified people Malhotra can find agree with him.

Speaker 2 They sure do that a lot. Before we get to our main event, we want to say thanks to our Area 51 all-access past patrons.

Speaker 2 That's KTA, the Fallacious Trump podcast, Stargazer97, Scott Laird, Dahlene, Stone Banana, Laura Williams, no, not that one, the other one, definitely not an AI overlord, 11 Gruthius, Chonky Cat in Chicago, has a full belly.

Speaker 2

Am I a robot? Captcha says no, but maintenance records say yes. Fredar Gruthius, Martin Fidel, and Dr.

Messi Andy. They all all subscribe to patreon.com/slash no rogan.

You can do that as well.

Speaker 2 All patrons get an early access to episodes as well as a special patron-only bonus segment each week.

Speaker 2

And this week, we're going to watch as the doctor pitches his brand new crowdfunded documentary, which exhibits a wow from Joe. Check it out at patreon.com/slash no rogan.

But for now, our main event.

Speaker 4 It's time.

Speaker 2

Huge thank you to this week's Veteran Voice of the Podcast. That was John Rogers.

He's just a guy, no podcast, but a big voice. Announcing our main event.

Speaker 2 Remember, you too can be on the show by sending a recording of you giving your best rendition of It's Time.

Speaker 2 Send that to no RoganPod at gmail.com. That's K-N-O-W-R-O-G-A-N-P-O-D at gmail.com, as well as how you would like to be credited on the show.

Speaker 2 So we're going to start, you know, we're not going to start talking about COVID right away, but most of the main event is going to be COVID denialism, COVID denialism, as well as anti-vaccination, COVID anti-vaccination.

Speaker 2 But in order to get there, we're going to start a little earlier in the conversation.

Speaker 2 Now, much of the first hour of this conversation is talking about statins, talking about cholesterol and health and diet, et cetera, metabolic health, which seems to be a theme with many of these people that he's sort of had on recently.

Speaker 2 But

Speaker 2 to sort of get to the COVID stuff, we have to start with a simple background, and then we're going to move on to that medical denialism. So this is the first clip.

Speaker 2 This is Dr. Malhatra's origin story.

Speaker 6 And how did you become this controversial COVID character?

Speaker 5 Well, it's interesting. My, I think, controversy with me probably started much many years ago.

Speaker 5 Probably I became sort of, I broke into the mainstream around sort of 2011 initially because I wrote an article, which was a front-page commentary in the Observer newspaper, which is part of the Guardian Group in the UK.

Speaker 5 Basically, as the cardiologist was saying, you know, why are we serving junk food to my patients in hospitals?

Speaker 5 And that was after I'd met with Jamie Oliver, who I'd written to. So that's I kind of started campaigning on the issues around obesity at that point.

Speaker 5 And not shortly after, not long after that, Joe, I then

Speaker 5 had sort of went into a deep dive to try and understand why we had an obesity epidemic. So what was driving that?

Speaker 5 What was the role of cholesterol in heart disease, over-prescription of statins, saturated fat, and essentially that culminated me publishing a piece in the British Medical Journal in 2013, October, basically, which was titled Saturated Fat is Not the Major Issue, and suggesting we should be focusing on sugar.

Speaker 5

We got it wrong on saturated fat. We're over-medicating million people, millions of people on statins.

Cholesterol is not that bad as a risk factor for heart disease.

Speaker 5

And that's really where I sort of broke into the mainstream. And that was, you know, the BMJ Press released it.

It was front page of three British newspapers.

Speaker 5 It was, I was on Fox News Chicago, CNN International. And that's really when I started my kind of activism and

Speaker 5 to try and fight back against medical misinformation and a kind of deep understanding that what was driving poor health for many, many people was biased and corrupted information that was coming from two big industries, big food and big pharma.

Speaker 4 So I think this is a pretty good illustration of who Milhotra is, though he is missing like a few beats here and there.

Speaker 4 So I found an article when I was researching this previously from 2007, from a local paper, the Manchester Evening News, where a 29-year-old Asim Milhotra was complaining that he'd got a medical degree, but he was finding it really hard to get a medical residency.

Speaker 4 And he was complaining that the system was flawed in trying to find your specialism because too few people were getting specialisms.

Speaker 4 And I only mention that because that was 2007 when he's in the local papers saying, I want a medical residency as a cardiologist and I can't get one.

Speaker 4 Four years later, just four years later, he's writing commentaries for newspapers about junk food and he's partnering with celebrity chefs.

Speaker 4 And that to me seems like a really fast progression from not a cardiologist to a cardiologist who's fighting the obesity epidemic in the front pages of the newspapers.

Speaker 4 I think that's quite a short time.

Speaker 4 So, yeah, someone who was a cardiologist for four years happened to be the one who saw the truth about statins in a way that far more experienced cardiologists and highly experienced medical researchers, who were actually the ones doing the research, not the cardiologists.

Speaker 4 The cardiologists interpret the research and kind of apply it to patients. They all couldn't see it, but this cardiologist who's been a cardiologist for about four years at most could see it.

Speaker 4 That seems unlikely.

Speaker 4 The alternative, though, is that he tended towards controversy and he felt the appeal of the limelight which is why he was writing in the newspapers why he was complaining in the evening news that he couldn't get a position and why he's writing the guardian everything he says there about statins we are going to come to that later in the toolbox segment so we're not going to talk in depth about statins at this point as you say but it is worth noting in this origin story He's listing primarily there.

Speaker 4 There's a couple of paper bits. But other than that, he's primarily listing his newspaper and his media appearances.

Speaker 4 and my in my opinion that's a massively important factor in understanding who alceem asim al-hotcha is and what he's about i did a a piece on him for my other show skeptics with a k a couple of years ago where i did a full background of everything i could find on him and i found more than 60 media stories that he'd written or was this was the source of was they were about him over a seven-year period which is a lot for a doctor 60 six zero stories in seven years that's not counting his tv appearances which i couldn't just find links to online So it really seems like he thrives in the limelight.

Speaker 4

And that's fine. I can't criticize someone for enjoying attention.

I've been in lots of newspaper stories too.

Speaker 4 But it does offer a bit of useful context as to why he might be, for example, on the biggest podcast platform in the world saying things that every other medical professional basically thinks is irresponsible nonsense.

Speaker 2 Yeah, I...

Speaker 2 When I heard him say, like, list the people who he was,

Speaker 2

the media outlets that he visited, he mentions Fox News Chicago. Well, you can get on Fox News Chicago with an oversized Illinois-themed quilt.

You don't necessarily need to have some breaking story.

Speaker 2

So, he's listing Fox News Chicago as if it's something big. It's not.

It's a local news channel. There is no Fox News Center, like national news center in Chicago.

It's just the local news nearby.

Speaker 2 It's not anything huge.

Speaker 4 You say it's easy to get on Cecil. You got to put your money where your mouth is and get us an interview on Fox News Chicago quite frankly.

Speaker 2 Start on that quilt right away. I bet you I'll be on it next week.

Speaker 2

You know, look, this is another Maverick. This is, this is, we have done this.

Marsha and I have been doing this for about a half a year now, and we've covered quite a few episodes.

Speaker 2 This is going to be, you know, we're in the 20s now, where we've listened to about 25 episodes total.

Speaker 2 And so far, you could certainly

Speaker 2 measure out a large percentage of the people who've been on his podcast as Mavericks, as people in their field who are bucking the entire system and saying, I have a different way of doing things.

Speaker 2 I have a different grand unified theory. I have a different,

Speaker 2 my way is so different because they're all corrupt. That's a real common theme on Joe's show.

Speaker 2 And it doesn't, it's not necessarily medicine, but it certainly in the shows that we're focusing on have been have been about medicine. And I think it's important to point this out.

Speaker 2 The problem is, is that

Speaker 2 There's a lot of people on the one side of the statin argument. And then there's another person on one side of the statin argument, a small group of people.

Speaker 2 And Joe is making it seem like those two sides are equal, that these two sides, we hear this a lot where it's like, we got to hear both sides.

Speaker 2 And you're like, well, both sides aren't equally weighted.

Speaker 2 It's like when we talk about climate change, there's, you know, a very high percentage of people, climatologists who believe climate change is real, that it's affecting our globe, that it's affecting currently how things, how weather is working in our current system.

Speaker 2

And then there's a group of people who are denialists. They don't don't believe that large body of science.

And we can't presume that both of them are equally right.

Speaker 2 We have to think about it in the sense that there's many people on one side who are coming to a conclusion and a tiny few on the other. So we can't look at them as if they're equal.

Speaker 4

Yeah, exactly. In Joe's mind, if you're in the minority, you must be onto something.

Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2 All right. So now.

Speaker 2

This is still the background of the show. We want to still lay out a little bit of groundwork before we get to the COVID stuff.

This is sort of how he views pharmaceuticals.

Speaker 2 And this is him talking about AstraZeneca and the CEO of AstraZeneca. And it's important, it's going to come up throughout this whole episode, but it's important to lay out early on in this show.

Speaker 5 But there is still now a push again to get more people on statins.

Speaker 5 And I suspect a lot of it is because, you know, if you think of the business model of the drug industry, it is to get as many people taking as many drugs as possible for as long as possible.

Speaker 5 2018, I am asked to go to the Cambridge University Union by the BMJ to be part of a team to debate with AstraZeneca. And I end up debating with the CEO of AstraZeneca.

Speaker 5

And the motion put forward, which was debated in Cambridge University, was from them, we need more people taking more drugs. That was their motion.

And

Speaker 5 it was just, yeah.

Speaker 5 So that's their business model, Joe. People need to understand what we're up against here.

Speaker 4

Okay, that isn't the business model of doctors, though. Even if that's a business model of pharmaceutical companies, you could argue that, yeah, maybe it is.

It's not the business model of doctors.

Speaker 4 And especially, I see the Mahotras from the UK, as am I. It's not the business model of the NHS to get more people on more drugs for longer.

Speaker 4 NICE, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and NHS England, those are the bodies in the UK that decide which treatments can be funded and prescribed with taxpayer money.

Speaker 4

They very specifically do not have this model. They're part of the government.

Their whole existence is to try and make sure that all treatments that are being funded by the public are cost-effective.

Speaker 4 And I know that because I've met with people from NHS England. I've sued NHS England for when they were spending money on stuff that didn't work, when they were spending money on homeopathy.

Speaker 4 I've brought legal cases against these bodies. They exist to make sure that money is being spent effectively.

Speaker 4 But in that, there's also cases where there are drugs that are effective, but at such a cost that they can't be justified on the public purse because the amount of benefit they will do won't outweigh the amount of money it costs.

Speaker 4 For example, I just had a quick check. In August of last year, there was an Alzheimer's drug called Lacanamab, and that was granted a license, an MHRA license, which means it could be given in the UK.

Speaker 4 But NICE ruled that the NHS weren't able to prescribe it because it was too expensive, that the benefit didn't justify the cost. That's the first example I found when I quickly searched.

Speaker 4 There are plenty of others. It's not uncommon.

Speaker 4 How do you square that with the idea of the business model of the entire industry here being as many people taking as many drugs as possible for as long as possible when those drugs are being turned down in some cases because they're too expensive.

Speaker 2 Yeah.

Speaker 2 I don't know if that's, and I also wonder too, because, you know, while Britain is going to have their cost cutting measures based on whether or not something's effective, I know that insurance companies aren't, they're not losing money.

Speaker 2 Like the insurance companies in the United States that we normally get our health care from, most people in the United States have some sort of insurance and which pays for our medical coverage.

Speaker 2 They're not looking to to get to get less money. It also seems like he's saying they're in cahoots, right? They're in cahoots with each other.

Speaker 2 They're, you know, behind the scenes, there's some, you know, some shady dealings going on. And I think you would hear a lot more about this from whistleblowers if that was the case.

Speaker 2 There's a lot of doctors out there that I think are very ethical, that if they were approached, they would immediately blow that whistle.

Speaker 4 Yeah, exactly.

Speaker 2 So let's talk about this, this, this thing he's claiming. He says

Speaker 2 he was invited by the Cambridge Union to do this debate. Now, the debate is, this house needs new drugs is the name of the debate.

Speaker 2 Now, it took me a while to find it because the only link I could find was to his website where he had his, you know, he was dunking on them, but their piece wasn't included.

Speaker 2 So I had to go do some searching in order to find it, but I did find it.

Speaker 2 And here's what I'm going to quote what the AstraZeneca guy says, because he's very specifically AstraZeneca CEO speaks and he he lays out his argument. And his

Speaker 2

claim is that they basically said we need need to get as many people on drugs as possible was what the AstraZeneca person said. Here is what they actually said.

Quote, today,

Speaker 2 what I want to do is support the motion is to make three points. The first one is today's innovative medicines are tomorrow's generics.

Speaker 2 The second point I want to make is that emerging new drugs are precise and they are effective and they are game-changing for patients. There is a new wave of tremendous new treatments that are coming.

Speaker 2 And the third is innovation. The drive for new drugs is risky, of course, but it also drives broader economic development and economic value creation.

Speaker 2 Now, should it be a shock that a CEO thinks the job they do is important? I don't think so.

Speaker 2 I think that that's probably, you know, if you ask people if the job they do is important, most people will probably say yes. And, you know, it feels like he's very much distorting the conversation.

Speaker 2 You know, their discussion was not about whether or not we should be taking more drugs. Instead, it's we need to create more and better drugs.

Speaker 2

And the opposition, the side that he was on, they said, we don't need more drugs. We need to use the ones we have better.

That was their argument.

Speaker 2 I just want to clarify that he's already kind of being sneaky with Joe. He's already saying, here's a thing that

Speaker 2 I was involved in. And here's this baseless argument that this group presented to show you how evil they are.

Speaker 2 They pull back the mask for a second and we got a chance to peek and see exactly how bad these people are.

Speaker 4 Yeah, exactly. And the thing to be clear here as well is is that we don't have to be on the side of the pharmaceutical companies to point out that Malhotra is being deceptive or being misleading here.

Speaker 4 Because we could say, you know, the pharmaceutical company is going to say, we need to spend more money developing new drugs in different ways.

Speaker 4 And we could say, well, actually, maybe there is an over-medication problem and maybe the pharmaceutical companies are making too much money. And I would agree with that.

Speaker 4 But Malhotra framed this as their motion was more people taking more drugs. And that is not what this CEO is saying.

Speaker 4 He's not just saying, oh, we just need everybody taking more drugs or more and more people taking more drugs. That's not what he's saying.

Speaker 4 They say they need better drugs and more, more better drugs that are going to be more effective, more innovative drugs. That's a very different argument.

Speaker 2

Okay, so now we're getting into the COVID stuff. This is about an hour into the show.

They start to really shift. We know how Joe feels about COVID and COVID medications and

Speaker 2

COVID vaccines. And this is him talking to Dr.

Malhatra about those things.

Speaker 6 Now, coming into COVID, did you have those initial fears or questions about the vaccine?

Speaker 5 At the very beginning, I had a little bit of skepticism about the efficacy of the vaccine because we know traditionally vaccines for respiratory viruses like influenza are not that great.

Speaker 5 But I didn't, so with all of this knowledge and background knowledge, I honestly treated vaccines, so the word vaccine, like holy grail.

Speaker 5 Despite all of this stuff around over-medicated population, all these pills people are taking, whether it's blood pressure pills they don't need or statins or even diabetes drugs that don't have much benefit for them and come with side effects, for me still, within all of that, vaccines are amongst the safest.

Speaker 5 So I never conceived of the possibility at all, actually, of a vaccine doing any harm.

Speaker 6 Even knowing that this is a completely different vaccine that

Speaker 6 nothing's ever been distributed like this with these numbers.

Speaker 5

So I know that now, but at the time, you know, I hadn't focused my attention specifically on the vaccines at all. So what you're saying makes sense.

But at the very beginning, you know,

Speaker 5 I deferred to vaccine specialists and immunologists and people I thought that, you know, didn't probably have conflicts who were all saying this is fine. So I hadn't looked at it in that much detail.

Speaker 5 And I just made the presumption that this was going to be safe. Don't know how effective it was going to be, but it was going to be safe.

Speaker 4

I should make a really quick point here. You can hear him saying that, you know, I just believe vaccines were great.

All this other stuff I wasn't sure about, but vaccines I thought was great.

Speaker 4 And you can either, you can take that at face value.

Speaker 4 But just listening to it through there what struck me was i've talked to lots of people who believe in ufols or psychics or something and they will always say to me hey i was the biggest skeptic in the world until this happened to me and then this persuaded me and it's a way of saying i wasn't crazy or anything it's just that this the evidence is so overwhelming and it really feels like that's what he's doing here like i was the biggest believer in vaccines imaginable

Speaker 4 until this happened and now i and now i uh i'm not anymore it feels like that's what he's setting up there it's a rhetorical device to get the audience on your side, and he's using it here.

Speaker 2 Yeah, that's an interesting point, Marsh.

Speaker 2 He says that traditionally vaccines against influenza are not great. What do you mean? Most years, they prevent like a ton of deaths.

Speaker 2 This year, we got the strain wrong, and there were, we saw that influenza deaths.

Speaker 2 outpaced COVID deaths for a while because there was the deaths went up by a large amount because we got the strain wrong.

Speaker 2 Sometimes that happens when we do these, but when we get the strain strain right, it's actually really, really useful and it helps prevent a lot of deaths.

Speaker 2

So him saying that traditionally they're not great. I'm sorry, man.

I get the COVID. I get the flu shot every year.

I don't want to get that stuff.

Speaker 4 Are you kidding me? Yeah, exactly. I've got a bunch of stats around this.

Speaker 4 Had he said, he says respiratory viruses, had he been saying things like colds or, you know, other forms of coronavirus in that kind of way, he'd have been right.

Speaker 4

There isn't a vaccine for the common cold or anything like that. Sure.

But he's talking about influenza. Well, he said at the beginning.

So he's not talking about last year. So this was 2023.

Speaker 4 but are you saying at the beginning he had fears um so what was the data saying about influenza vaccines at the the beginning of the pandemic well according to a 2020 paper in the journal of infectious diseases looking at data from the us

Speaker 4 the overall vaccine effectiveness against influenza viruses was 41 percent and as you say there's different variants each year in that year the effectiveness was it was 33 percent against influenza b viruses 40 percent against influenza a h1n1 viruses and some other kind of uh effectiveness against some other viruses too.

Speaker 4 Around the same time, studies from the UK also showed that in children aged 2 to 17, the flu vaccine presented 66 cases of flu, sorry, 66% of cases of flu between 2016 and 17, 27% between 2017 and 18, and 49% between 18, 19.

Speaker 4 So there is this variability, but it's pretty decent.

Speaker 4 Those numbers that are low, it might sound like some of those numbers aren't great, but you also have to bear in mind that a vaccine doesn't have to be 100% effective effective to have a huge impact on slowing the spread.

Speaker 2 Great point.

Speaker 4 So there was a study from 2024 that I found that said that if someone in house in the household contracts flu, there's a 20% chance that someone in the same household will get it from them.

Speaker 4

They'll be passed along. It's just one study.

I'm just going to use it as an illustration of the maths.

Speaker 4 If that second person gets flu on the 20% chance, they would then have a 20% chance of giving it to someone else.

Speaker 4 which means the first person had a 4% chance of giving it to the third person, essentially.

Speaker 4 If those people were vaccinated and you add in like a level of vaccine there, like a vaccine with say a 40% efficacy, your chance of getting to the first person will be 12% and the second level spread would be 1%.

Speaker 4 So you're already massively slowing down the spread, even with relatively like average effectiveness of vaccines.

Speaker 4 Data published by the UK Health Security Agency on May 22nd of this year, in fact, so very, very recent, it showed that the flu vaccine was estimated to prevent around 90, between 96,000 and 120,000 people from being hospitalized in England during winter with the flu.

Speaker 4

So 18 million doses of flu vaccine, about 100,000 people prevented from being hospitalized. So really extreme stuff.

That's not even counting the cases that were prevented.

Speaker 4 So for a doctor to be saying that we know that traditionally the flu vaccines aren't very good suggests he's either not familiar with the actual data in the research or he's ideologically blinded to it.

Speaker 4 It's one of those two things.

Speaker 4 And that makes it really worrying that he then casually throws out that neither statins nor diabetes medications are beneficial or worth the side effects.

Speaker 4 So he's really going contrarian on several different strains at once here. Yeah.

Speaker 2 And, you know, this number is going to be important to remember as we work our way through this. There have been 13.64 billion COVID doses distributed worldwide.

Speaker 2 So it's important to remember that number as we work our way through because the things that they're saying, the number of people we would see with these problems would be amplified so much because it's it's at this point it's almost twice the population of the earth you know that's how many doses have been given out to people it's a lot of people that have gotten it and a lot of doses of this covet shot have gone out to people Yeah, and the COVID shot was pretty effective.

Speaker 4 So I looked at a 2022 report from the Office of National Statistics in the UK, which looked at census-level data for 42 million UK citizens to check the effectiveness of the vaccine.

Speaker 4 And what it found was the vaccine was effective against hospitalization for COVID. It was 52% for the first dose, 55% for a second dose, 77% effective against hospitalization once you had the booster.

Speaker 4 When it looks at mortality, so actually dying from COVID, first dose gave you 58% protection, the second dose, 88%

Speaker 4 protection, and the third dose gave you 93% protection. Now, the effectiveness decreases after time.

Speaker 4 It's been a while since you've had a booster, which is why you keep needing boosters. But we're talking about incredibly effective vaccines here.

Speaker 4 We're not talking even about the 40% that you were seeing with the flu. 93% effective against mortality is massive.

Speaker 2 Next up, they're going to start talking a little bit about obesity and how that affects COVID.

Speaker 5 So I noticed this link with obesity and I said, listen, you know, this is my work over many years.

Speaker 5 One of the things that I also advocate for is that to for people to understand that if you change your diet, just within a few weeks, depending where you're starting from, you can potentially even send your type 2 diabetes into remission.

Speaker 5 You can reverse the most important risk factors for heart disease. So, I knew that if people were told that when this virus was, you know, when the pandemic started, this was an opportunity.

Speaker 5 Actually, we already had the slow pandemic of chronic disease, which we hadn't effectively curbed anyway.

Speaker 5 This is a great opportunity for government to say, listen, guys, now this is a time to sort your diet out, take vitamin D, you know, really just optimize your immune system. And it wasn't happening.

Speaker 2 Okay, so for a little background here, the doctor,

Speaker 2

he wound up, he's creating a book. He wrote a book in August of 2020.

Now, bring yourself back to August of 2020. There's no vaccine.

Speaker 2

They're in trials, I think, at that point, or they're just starting trials at that point. There's no vaccine.

And he's, this is August of 2020. So this is his book, 21-Day Immunity Plan.

Speaker 2

Here's the book jacket, guys. Quote, Dr.

Asim Malhatra is a leading NHS trained cardiologist and a pioneer of lifestyle medicine.

Speaker 2 Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease are indicators of poor metabolic health.

Speaker 2 The good news is that in just 21 days, we can prevent, improve, and even potentially reverse many of the underlying risk factors, end quote.

Speaker 2 So that is from his book jacket that he released right during the probably some of the worst times of COVID.

Speaker 4

Yeah, absolutely. It was published, as you say, August 2020.

That means it was written, proofed, accepted, laid out and printed within the first five months of the pandemic.

Speaker 4 So you've got to wonder how much research time actually went into writing it. It's barely 21 days of writing once you take the rest of the process into account.

Speaker 4 And it'd be really easy for someone to see this as a somewhat cynical grab for attention and acclaim at a time of great crisis.

Speaker 2 we're also talking to much of this podcast, much of Joe's podcast up till this point is talking about money and how money is changed.

Speaker 2 It's really just the main reason why these pharmaceutical companies are doing the things they're doing, why they're pushing all these medicines, why statins are through the roof, why everyone's on them, et cetera, et cetera, is because they just want to keep on raking in the cash.

Speaker 2 And the reason why COVID vaccines are the way they are is because they want to rake in the cash.

Speaker 4 Well,

Speaker 2 we spend all this time

Speaker 2 demonizing money and research.

Speaker 2 Why is his book in august 2020 any different than that you have a monetary incentive to deceive people as well so should we just should we put you in the same bucket i think like it's important to point this out as a way i mean and it's it's a little bit of hypocrisy and normally we don't do that sort of thing but i think it's important to point it out here because you know there's a there's a good possibility if that's if if if we believe that that's how human nature works for everybody does it work the same way for you doctor yeah yeah exactly And bearing in mind here, Asim Mahotra is a cardiologist.

Speaker 4 The book jacket even says an NHS-trained cardiologist, as in trained by the NHS, which makes it clear, not working for the NHS. He's not an NHS cardiologist, but he was trained by the NHS.

Speaker 4 I don't know why NHS-trained is in there.

Speaker 4 I don't know why that matters other than sort of essentially trading off the good reputation of the NHS in that place. But he's a cardiologist who got famous essentially writing diet books.

Speaker 4 And then when the pandemic came along, he wrote a diet book. Cardiologists are not dietary specialists.

Speaker 4

And his argument, if you follow it, is essentially that people with diabetes and heart disease were more at risk of getting complications from COVID. Okay, that bit's not wrong.

That's true.

Speaker 4 But his solution is you should go on a diet to reverse your diabetes in order to lower your COVID risk.

Speaker 4 And then he says something about optimizing your immune system with your diet, but he's not got anything to back that up.

Speaker 4 He's just throwing it in because not everybody has heart disease and not everybody has diabetes as a a risk factor for COVID. So you need, you don't want to limit your audience by that much.

Speaker 4 But also, like the fact that he's saying that you should be trying to

Speaker 4 handle

Speaker 4 those diseases in order to lower your COVID complication.

Speaker 4 It's a kind of a Robe Goldberg machine approach to COVID prevention, just to get around the fact that if you took a vaccine that is demonstrably safe and effective, that will lower your risk.

Speaker 4 It just will do that.

Speaker 2 And you don't even have to eat Italian coconuts. You can do other stuff, right? You can have pasta.

Speaker 4 You're allowed pasta.

Speaker 2 All right. We're going to take a short break.

Speaker 4 We'll be back right after this.

Speaker 7 Making the holidays magical for everyone on your list? It's no small feat. But with TJ Maxx, your magic multiplies.

Speaker 7 With quality finds arriving daily through Christmas Eve, you'll save on Lux Cashmere, the latest tech, toys, and more.

Speaker 7

So you can check off every name on your list and treat yourself to a holiday look that'll turn heads. Now you know where to go to make all that holiday magic.

It's TJ Maxx, of course.

Speaker 7 It's shaping up to be a very magical holiday.

Speaker 8

Big things are happening at your local CVS. Extra big.

So hurry on over because extra big deals are here. These are deals so extra that they absolutely cannot be missed.

Speaker 8 And every two weeks, there's gonna be more. So you've gotta keep coming back so you can keep on saving on all the brands and products you and your family use every day.

Speaker 8

And speaking of saving, extra care is the way to save at CVS. So use your extra care card to unlock savings every time you shop.

And if you're not a member yet, now's the time to join.

Speaker 8

And the best part, it's completely free. Just sign up online or in-store and you'll start saving instantly.

And always be sure to check the CVS Health app for deals and savings.

Speaker 8 Visit your local CVS store or cvs.com slash extra big deals to shop this week's deals and stock up on your favorite products.

Speaker 9

What does Zinn really give you? Not just hands-free nicotine satisfaction, but also real freedom. Freedom to do more of what you love, when and where you want to do it.

When is the right time for Zen?

Speaker 9

It's any time you need to be ready for every chance that's coming your way. Smoke-free, hassle-free, on your terms.

Why bring Zen along for the ride?

Speaker 9 Because America's number one nicotine pouch opens up something just as exciting as the road ahead. It opens up the endless possibilities of now.

Speaker 9

From the way you spend your day to the people you choose to spend it with. From the to-do list right in front of you to the distant goal only you can see.

With Zen, you don't just find freedom.

Speaker 9 You keep finding it. Again and again.

Speaker 9 Find your Zen. Learn more at zen.com.

Speaker 4 Warning.

Speaker 9 This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical.

Speaker 10 Every year, I promise myself I'll find the perfect gift.

Speaker 4 Something they'll actually use.

Speaker 10

And love. This year, I found it.

The Bartesian Cocktail Maker.

Speaker 4 Oh, that's the one that makes cocktails at the push of a button, right? Exactly.

Speaker 11 Over 60 bar quality drinks from martinis to margaritas. Perfectly crafted every time.

Speaker 10 I got one for my sister, and maybe for myself too.

Speaker 4 Smart. It's the season of giving and sipping.

Speaker 11 And right now, you can save up to $150 on Bartesian Cocktail Makers.

Speaker 4 That's a real holiday mirror.

Speaker 10 Because the best gifts bring people together and make the holidays a little easier.

Speaker 12

Give the gift of better cocktails this season with Bartesian. Mix over 60 premium drinks at the touch of a button.

Save up to $150 on Bartesian Cocktail Makers. Don't wait.

Speaker 12

This offer ends December 2nd. Shop now at Bartesium.com/slash Brinks.

That's B-A-R-T-E-S-I-A-N.com slash Springs.

Speaker 2 All right, we're back. Let's jump right back in.

Speaker 2 This next bit is talking about ambulances, and it's talking about ambulances and his father, who had gotten the shot, the COVID shot, and his father passed away and had a heart attack.

Speaker 2 And so this is that story as it unfolds on the podcast.

Speaker 5 I got a phone call from somebody senior in the health department linked to the government called NHS England, and she was crying. She was a nurse, senior nurse, and she knew my dad.

Speaker 5 And she said, Seems something I've got to tell you. I said, what is it? She says, the Department of Health, the government, had known for at least for several weeks throughout the whole country that

Speaker 5 ambulances were not getting anywhere close to their targets for treating people for heart attacks or cardiac arrest, but had made a decision decision to deliberately withhold that information.

Speaker 5 And for me, that, you know, that, that was,

Speaker 5 that was quite upsetting because if I had known that, if we had known that, I wouldn't have asked him to call an ambulance.

Speaker 5 You know, the neighbors could have, the nearest hospital was like a five-minute drive, Joe. They would have, you know, he would have, somebody would have taken him there.

Speaker 5 Even if he had a cardiac arrest en route, they would have been able to get to Diffrabrader and he probably would have survived. So I thought, this is, you know, I need to do something about this.

Speaker 5

People need to know. Because it was still kept hidden.

So I, I, with a journalist in the, in the UK called Paul Gallagher with the eye. I've done a lot of work with him, great journalist.

Speaker 5 He then started doing in freedom of information requests, getting information from the ambulance service, trying to find out what happened, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker 5

And we determined that this was the case, that there was all these delays and it had been going for a long time. And then I wrote an article in the eye newspaper.

It became a BBC News story.

Speaker 2

So the previous portion of this tape is him talking about how his father had a COVID shot. His father developed a heart condition.

He was talking about how robust his father was, how

Speaker 2

he was in his 70s, but he was playing badminton. He was one of these guys who was constantly out walking and very active.

And he wound up having a heart condition.

Speaker 4 Now,

Speaker 2 Malhatra is trying to connect this father's heart attack with the COVID vaccine. That's what he's doing throughout this whole piece.

Speaker 2 And here he's talking about how he had gotten a phone call from his dad who said he wasn't feeling well. So he told his dad to call an ambulance.

Speaker 2

And then he gets this information that says, hey, the ambulances weren't running correctly. And so I looked it up.

I was like, well, when did this happen?

Speaker 2 And why, why would that, is there, is there any other reason, any extenuating circumstances that could be happening? Well, it turns out it's during the Delta variant of COVID. So it's 2021.

Speaker 2

It's right during the Delta variant. It's the third wave of daily infections began in July 2021.

due to the arrival of the rapidly spread and highly transmissible SARS-CoV Delta variant. So, you know,

Speaker 2 mass vaccination continued to keep deaths and hospitalization at a much lower rate than previous waves.

Speaker 2 The infection rates remained high and hospitalizations and deaths rose into autumn, which is when this happened.

Speaker 2 So you could expect that there would be higher than normal uses of ambulances during this time.

Speaker 2 There was a lot of people getting COVID and a lot of people needed to get transported to hospitals to stabilize them.

Speaker 4

Yeah, absolutely. There were also issues of funding in various other ways.

There'd been a funding crisis on the NHS under the previous government, the Tory government at the time, that

Speaker 4 ambulance times were rising generally because it was getting harder and harder to find enough staff because of the amount of money that was being done there.

Speaker 4 So it was also, there was a financial and economic thing going into the pandemic that was causing an issue. But he uses his, he talks about his dad's death as being incredibly impactful.

Speaker 4 I mentioned the study that he published in the Journal of Insulin Resistance. That study was a case study of a particular patient who got vaccinated and had a heart attack.

Speaker 4 And he didn't declare throughout the publishing of that study that the patient was his dad. He did a case study about his on and didn't mention that as a conflict of interest.

Speaker 4 I would argue that is quite a substantial conflict of interest if you're that close to that particular story.

Speaker 4 And I'm not going, but I'm not going to knock him for how his dad's death affected him.

Speaker 4 That's going to be an incredibly hard thing for anyone to cope with at any time, especially finding out that if he had been able to get to a hospital, the survivability would have been much higher.

Speaker 4 That's going to be an incredibly impactful thing. But it does feel like it's a major influence on how Mahotra went on to deal with COVID and the vaccine.

Speaker 4 And it's worth pointing out the timeline of it here. His dad died in September 2020,

Speaker 4

2021, rather. That's a year after he published his book on immunity and diet.

So it feels like he was already on a COVID contrarianism path before this happened. So it's not like he was

Speaker 4 a doctor who was parroting the mainstream narrative until this came along. He was already plowing his own furrow.

Speaker 4 It's also really hard when he's telling this story of his father's death a few years later, after he's processed it, after he's recontextualized it to fit his own personal journey.

Speaker 4

We do this with our memories all the time. We tell stories and we put things into an order.

We put the pieces together.

Speaker 4 And it seemed familiar with me because if you remember the Piopi diet, that Mediterranean diet book he was talking about.

Speaker 4 In the publicity around that campaign, around that book coming out, the campaign work he was doing with Jamie Oliver and things like that.

Speaker 4 He was attributing, he was talking a lot in the newspapers about his mum's death, which he specifically attributed to her vegan diet, her vegetarian diet, rather, not having enough fat and protein.

Speaker 4 So he's saying, well, my mum died because she didn't know that she should have been following my diet book.

Speaker 4 And then he's saying, well, my dad died because he's doing, he's, because of this thing that I'm then going to take on as a campaign. So it does feel a lot like.

Speaker 4 the personal tragedies of his life keep aligning with his off-the-beaten path views pretty closely or maybe influencing them.

Speaker 4 And the last thing I'll say that he mentions in the interview, and again, it may be somewhat pertinent to a small degree.

Speaker 4 He says that he got a call from a senior nurse at NHS England who knew his dad pretty well. That's because his dad was formerly the vice president of the British Medical Association.

Speaker 4

And a very, very well-known doctor. And when he talks about his dad in this interview, he says he was super competitive.

Me and him were always really competitive.

Speaker 4

We were playing badminton at really high, kind of competitive. Oh, that's how fit he was.

But he talks about how competitive his dad was. And his dad was the vice president of the BMA.

Speaker 4 And growing up with a father who was such a famous doctor that when he died, he got an obituary in, I think, The Guardian, or certainly one of the leading newspapers in the country, published an obituary to his father when he died.

Speaker 4 I'm not one to diagnose people, but it does feel like having such a well-respected, influential father in the medical field is going to have some degree of impact.

Speaker 4 And it's maybe not a surprise to me that even early in his career, Asim Mahotra is looking to be the one cardiologist who figures out that statins are a lie.

Speaker 4 He's the one cardiologist or one of the few, the few doctors who are able to point out the flaws in the vaccines in this way. It feels like he wants to be blazing a name for himself.

Speaker 4 And that may be completely unintentional, but it sort of feels like it's worth commenting on.

Speaker 2 The conversation here continues around COVID. And now they're going to talk about how the COVID vaccine doesn't stop infection.

Speaker 6 And because it wasn't scientific, and because there was now evidence that it didn't stop transmission and it probably wasn't going to stop infection, what was the narrative that you were given as to why this should still be promoted?

Speaker 5 Well, there wasn't really anything, Joe. It didn't make any sense to me.

Speaker 5 The chief medical officer was still saying the same thing, though.

Speaker 5 So he was still tweeting out, even before they decided they were going to, you know, and even after they overturned this mandate decision for healthcare workers, he was tweeting out the best thing you can do as a doctor to protect your patients is get vaccinated with a COVID vaccine.

Speaker 4 Yeah.

Speaker 5 It didn't make any sense.

Speaker 5 It was almost like, to be honest, this was the kind, the kind of narrative that was coming out was essentially the narrative of the drug companies, but coming through so-called credible voices.

Speaker 5 You know, it wasn't, it wasn't in keeping with the evidence. It didn't make any sense.

Speaker 2 I can kind of forgive Joe here for not understanding how medicines work in some ways, because Joe is talking at the beginning and he's saying, look, there's no evidence that it stopped transmission.

Speaker 2

It probably wasn't going to stop an infection. You know, there was a chance that it wouldn't stop infection.

And they were still going to give it out. They're still going to promote it.

Speaker 2

They were still. And so I can kind of forgive Joe a little bit for not understanding this.

But this is very much,

Speaker 2 it screams to me, Marsh, like conspiracy theory. It sounds so much like, well, jet fuel can't melt steel beams.

Speaker 2 You're like, yeah, jet fuel doesn't have to melt steel beams in order for it to actually be damaging to a building. And the same goes for how infections work.

Speaker 2 It doesn't have to prevent it completely in order to slow it, right? In order to slow the chance that it goes out. They make it seem like it was an all or nothing thing.

Speaker 2 If it lessens transmission, if it lessens symptoms, if it lessens your chance of getting severe COVID, those are all really good things that a vaccine can do.

Speaker 2 And I don't think, and I think that they were misconstruing some of the comments from early on and early studies and making them making them and saying, oh, well, it should have prevented it.

Speaker 2 And since it didn't, it didn't actually work.

Speaker 4 Yeah, absolutely. It's black and white thinking.

Speaker 4 They're talking about the mandate for healthcare workers to get vaccinated as well.

Speaker 4 And again, when Malhofta talks about this, he talks about personally meeting with the health secretary, Sajid Javed, to try and persuade him not to bring in this mandate.

Speaker 4 So again, he's talking about the connections that he has. He's incredibly well connected.

Speaker 4 I don't know whether that's through his advocacy work or through his family family connections through his very influential father i have no idea but he's meeting incredibly serious people here um but it makes sense to have a uh if not a mandate then a strong encouragement towards healthcare workers you want to have them vaccinated because if it stops them getting infected they're not sick in the first place to pass it on to vulnerable patients so maybe it's not going to stop you transmitting but if it stops you getting infected you can't you can't transmit something you aren't infected with and maybe it doesn't stop you getting infected but it stops it being too severe, which means, for example, you might be off work for a shorter period of time, meaning our healthcare workers can still be working helping people during a healthcare crisis.

Speaker 4 So maybe instead of taking seven days off work with COVID, you take three days off because your symptoms aren't as bad.

Speaker 4 But all of this just gets written off as it sounded like the narrative of the drug companies.

Speaker 4 And that's because Marjoto doesn't want Joe or his audience to consider why the people in charge of health might be advising people who see vulnerable patients a lot to get vaccinated.

Speaker 4 Don't consider that. Just assume that it's the narrative of the drug companies and therefore bad.

Speaker 2 Okay, so now we're going to talk about side effects of the vaccine and mRNA.

Speaker 5 The key bit of data, right? People say, oh, lots of data, cherry-picking, blah, blah.

Speaker 5 Just one bit of data alone should be enough to people to stop and think, oh my God, this is just unbelievable.

Speaker 5 So in the summer, towards the end of last year, second half of last year, the journal Vaccine, peer review, this is like the highest impact medical journal for vaccines, right?

Speaker 5 They published a reanalysis of Pfizer and Moderna's original double-blinded randomized control trials.

Speaker 5 So this is the level, the highest quality level of evidence, okay, with all the caveats, drug industry sponsored, all that stuff, right? But still what we call the highest quality level of evidence.

Speaker 5 Done by independent researchers, Joseph Freeman from Louisiana, he's an ER doctor, clinical data scientist, associate editor of the BMJ, Peter Doshi, Robert Kaplan from Stanford, right?

Speaker 5 Some very eminent in terms of eminence of integrity, right? I'm not for eminence-based medicine, but I'm for people who have eminence of integrity, right? They published this reanalysis.

Speaker 5 And what they found was this, in the trials that led to the approval by the regulators, we'll get onto regulators in a minute around the world, you were more likely to suffer a serious adverse event from taking the vaccine, hospitalization, disability, life-changing event.

Speaker 5 than you were to be hospitalized with COVID. So what that means is it's highly likely likely this vaccine, mRNA vaccine, should never have been approved for a single human in the first place.

Speaker 5 And that rate of serious adverse events, Joe, is one in 800. And it's at least one in 800 because that just covers the first two months of the trial.

Speaker 4

At the very start there, he says, they say it's cherry-picking, blah, blah, blah. You can't blah, blah, blah away cherry picking.

We're going to explain in the toolbox why.

Speaker 4 That's going to be something we're going to focus on a lot. But he says, it should just take one data point to make you stop and question things.

Speaker 4

Well, no, one data point alone can't be enough when there's a load of data saying the opposite thing. That is cherry picking.

That is why you get accused of cherry picking. And we will come to that.

Speaker 4 But yeah, we've got the paper there. You actually found the paper that he's talking about as well, didn't you?

Speaker 2 Yeah, I did. I found it and it looks like it's discredited, Marsh.

Speaker 4 Yeah, it doesn't look like it is the highest quality level of evidence, as he said.

Speaker 4 I read

Speaker 4

some of the critiques. We'll put a couple in the show notes, of course.

So there's loads of links.

Speaker 4 And this show notes is gonna be filled with a lot of links to studies and various other things so by all means check those out to make sure that we're that so you can see the evidence we're directing people towards so this rear reappraisal so Pfizer and and the drug companies had put out the studies originally other people come along looked their original data and reappraised it to see what was going on and that's where they found apparently all these serious issues well part of the issue with that reappraisal is They looked through all of the side effects and they reclassified them as to which ones they felt seemed serious.

Speaker 4 But the problem is they did that in an unblinded way. So they didn't look at a list of 10,000 side effects and say all of these,

Speaker 4 every kind of heart issue goes in this category. What they did is they looked through all of the side effects in the vaccine arm and then

Speaker 4 decided which ones were serious. And then they looked through all the side effects in the placebo durse ones and did the same thing.

Speaker 4 This is going to be a massive source of bias because in the vaccine arm, specifically they classified the words chest pain as which were reported as side effects.

Speaker 4 They classified that as pericarditis, which is, sure, pericarditis is a form of chest pain, but it's not the only chest pain.

Speaker 4 To assume that every chest pain is pericarditis is going to massively overstate that particular side effect.

Speaker 4

In the placebo arm, they downgraded syncope of the heart to arrhythmia. Arrhythmia is way less serious than syncope.

It's a form of syncope, but it's a less serious one.

Speaker 4 So again, you're taking the things that could be indicated of something serious in the placebo arm and you're downplaying them because it was a placebo. Of course, it wasn't anything too bad.

Speaker 4 In the vaccine arm, they categorized abdominal pain as colitis or enteritis, when it could just be a poly stomach. It could be all sorts of things that you might just get in life.

Speaker 4 So essentially, side effects in the placebo arm were way less likely to be considered serious because they were in the placebo arm.

Speaker 4 And therefore, they concluded there were more serious issues in the vaccine arm. That's not surprising in any way.

Speaker 4 And the other thing that's that's interesting, and I had to read a couple of things to figure this out, Mahatra says very specifically, they found you're more likely to suffer a serious adverse effect from taking the vaccine than you were to be hospitalized with COVID.

Speaker 4 So first of all, you know, they took all of the COVID-related adverse effects out of the data. So anything that was a sign of COVID, they removed.

Speaker 4 But that's not ideal because you're going to get a load of those in the placebo arm. So anything that hospitalized somebody for COVID in the placebo arm was taken away.

Speaker 4

You don't get to see that there. So that's removing the efficacy of the vaccine.

But even more importantly, you hospitalize patients, but you count symptoms.

Speaker 4

So for example, person A goes to hospital with COVID. He's one person.

Person B doesn't go to hospital with COVID, but he has got a headache and a sore arm and a bit of fatigue and an upset stomach.

Speaker 4 He's four symptoms.

Speaker 4 So instantly you have it here

Speaker 4

as to Waymore. So yeah, I think that's a really interesting.

But he's fine. There's nothing wrong with him.

Speaker 4 But he's got all these symptoms from from the vaccine but they're all small symptoms but if you're overegging how big those are you're going to make it look like four serious adverse events it's one person with four different things going on none of which are that serious yeah and he uses the number in this he says one in 800

Speaker 2 uh this is serious adverse events at least one in 800 that covers the first first two months and this is he's talking about serious adverse events he's talking about hospitalization from the from the vaccine there were i mentioned it earlier 13 plus billion doses of this vaccine went out.

Speaker 2

That would mean over 16 million people would have been hospitalized or had serious adverse effects from that. We didn't notice that.

That's something you'd notice. He's saying it's a big number.

Speaker 2 It is not that big a number.

Speaker 4

No, exactly. Unless.

you've just exaggerated what a what counts as a serious adverse effect.

Speaker 4

You do that. You've gone from abdominal pain to colitis.

There aren't 16 million people with colitis, but there might have been quite a few people who had a bit of a dicky

Speaker 4 stomach at some point during the vaccine trial.

Speaker 2 We're going to continue on in this next club with more side effects.

Speaker 5 But then there is the fact that, you know, we consider vaccines to be completely safe traditionally. 1-800 is a very, very high figure.

Speaker 5 We've pulled other vaccines for much less.

Speaker 5 1976, swine flu vaccine was pulled because it was found to cause a debilitating neurological condition called Guillen-Barry syndrome in about one in 100,000 people.

Speaker 5 Rotavirus vaccine pulled in 1999, suspended suspended because it was found to

Speaker 5

cause a form of bowel obstruction in kids in one in 10,000. This is at least one in 100.

I mean, it's a no-brainer. So the question then is, why have we not paused it? What's going on here?

Speaker 5 And I think the barrier that we've got, Joe, to deal with with a lot of people who are not enlightened or is awake or familiar or understanding this information, it's a psychological barrier.

Speaker 5 It's not an intellectual one.

Speaker 5 Right.

Speaker 5 This is willful blindness, you know, a concept, a psychological phenomenon which we're all capable of in different circumstances, where human beings turn a blind eye to the truth in order to feel safe, avoid conflict, reduce anxiety, and protect prestige and fragile egos.

Speaker 4

So, yeah, one in 800, it is indeed a very, very high figure. It's also not true.

So, we're building on this kind of castle built on sand, essentially. Yeah.

And

Speaker 2 can you compare these if the harms are different? right? We're presuming, presuming that there's harms.

Speaker 2 If the harm of her COVID vaccine is less than the syndrome he suggests, that Gillian-Baer syndrome,

Speaker 2 can we make this comparison?

Speaker 2 Is this apples to oranges? Is that what we're doing here?

Speaker 2 You know,

Speaker 2 for him to say something like a debilitating neurological condition caused by a different vaccine and then to immediately say, and he's like, and that's why it was pulled.

Speaker 2

And now we say, oh, well, it's a, you know, there's, there's debilitating symptoms here, but I'm just not mentioning what those are. And that's why it should be pulled.

That's, I don't believe that.

Speaker 2 I don't believe that those two things are comparable.

Speaker 4

No, exactly. And he says the barrier is psychological and not intellectual.

He says it's will for blindness. And I agree.

Speaker 4 But in my opinion, it's Malhotra who is the one who is willfully and psychologically ignoring the data because there is no question that he is smart enough to understand the stats. He absolutely is.

Speaker 4 If he came across these stats.

Speaker 4 without his ideological bias, if these exact same statistical patterns were available for something that he didn't have an invested position in, he would recognize the flaws here.

Speaker 4 And I'm also just going to say here, neither of these men should be calling out fragile eagles. They just really shouldn't at all.

Speaker 4 Okay.

Speaker 2 Now we're going to talk about going into a hospital during COVID.

Speaker 5

And I'm a numbers guy. I think numbers are important.

I think when I have conversations with patients, I want to break numbers down in a way that they can understand.

Speaker 5

So we all had a very grossly exaggerated fear. Many people did, maybe not you, Joe, but many people did, of the virus at the very beginning.

I did at the beginning.

Speaker 6 Yeah.

Speaker 5 One survey in the U.S. suggested that 50% of American adults thought that their risk of being hospitalized with COVID was 50% one in two, when the real figure at that time was about one in 100.

Speaker 5 In fact,

Speaker 5 I did a subsequent analysis in my paper because a lot of my paper also focused on the fact of lifestyle and obesity and all those things we can do to improve our immune system.

Speaker 5 And at the very early stages, Wuhan strain in the UK, looking at middle-aged people, the risk of hospitalization if you were an obese sedentary smoker from a poor background, socioeconomic background, class, was about one in 350 or something like that.

Speaker 5 If you were active, not overweight, non-smoking, you know, healthy diet, all that kind of stuff, your risk of hospitalization was almost four to five-fold less, five-fold less, so one in 1500.

Speaker 4 Wow.

Speaker 5 Yeah, massive difference. So again, that reinforces...

Speaker 6 That is not the way it was described.

Speaker 4 No, not at all.

Speaker 5 But those figures are important because without understanding the numbers involved, the public and doctors are vulnerable to exploitation of their hopes and fears by political and commercial interests.

Speaker 5 And that's what happened.

Speaker 4 Wow.

Speaker 4

I think there's so much to talk about here. He's talking initially about the very start of the pandemic.

People thought there was a 50% chance of being hospitalized. We didn't know anything.

Speaker 4

That's where fear comes from. Like you didn't know better at the time.

We didn't know anything.

Speaker 4 Sure, as it panned out, it wasn't as likely to send us to hospital at that, but it's not unreasonable to be unsure about a disease that we know nothing about, because if it had have been that, half of the people wouldn't be around to say, boy, I was wrong about how

Speaker 4

likely I was to be hospitalized. But then he ends with, like, he gets towards a point where 15, it's only one in 1500 people.

That's still quite a lot of people. That's still quite a lot of people.

Speaker 4 The UK has a population of 70 million. One in 1,500 is still a load of people going to be hospitalized.

Speaker 4 Hospitalization doesn't mean, you know, if it's one in 1500 people gonna catch COVID, but gonna have a really shitty time for a week at home and be off work and feel like crap.

Speaker 4

Okay, that's maybe not that bad. But one in 1500 being hospitalized implies that it's maybe one in 200 going to get it and have a seriously bad time.

And

Speaker 4 the hospitals would be overwhelmed if one in 1500 people were in hospital at any given time. Sure, sure.

Speaker 4 So the UK has a population of 70 million people by April 2024, we had 25 million confirmed COVID cases. So your risk of actually catching it was one in three, slightly less given re-infection.

Speaker 4 So we're not talking the one in 1500, that's hospitalization, but one in three chance of getting it.

Speaker 4

I still, I think it's not unreasonable to be worried about that, especially at a time when we didn't know how serious it was. We also in the UK, we saw 232,000 deaths.

on a population of 70 million.

Speaker 4 So your risk of dying of COVID, not hospitalization, actual death of COVID was one in 300. That's not in terms of like, if you caught it, your risk of dying.

Speaker 4

One in 300 people in the UK died of COVID on those stats. I think that's, yeah, that's true.

70 million population, 232,000 deaths. One in 300, that's an incredibly high number.

Speaker 4 You were five times more likely to actually die of COVID than he claims your chances of hospitalization were. If I've done the maths wrong there, please, somebody let me know.

Speaker 4 I have checked that a couple of times, but know,

Speaker 4

it stands to reason. 232,000 is about a quarter of a million.

So, and we've got 70 million in the UK. Now, these figures include the year following this interview.

Speaker 4 It's following the interview, the 2023 interview that they're talking about here. So you could say they're reflective of information that he didn't have.

Speaker 4 But actually, if you look at the data up until the point of this interview, rather than having 25 million cases, we had 24.5 million cases.

Speaker 4 And rather than 232,000 deaths, we had 225,000 deaths. So the data that I'm citing, those figures are available and they were reasonable at the time.

Speaker 4

But in the year after this interview went out, the UK had a further 500,000 cases and 6,000 more deaths. So why were there so few deaths by comparison? The vaccine.

That's why we had

Speaker 4

so many fewer cases and so, so many fewer deaths. Because the vaccine worked.

And we've got graphs of this that we'll put up on the YouTube version.

Speaker 4 In fact, if you look at how the daily cases, the new new daily cases stack up throughout the course of the pandemic, you see the graph of those against the daily reported deaths throughout the course of the pandemic, that spikes on death are in April 2020 and January 2021.

Speaker 4

That's when they peak. The peak in new cases is January 2022, and it's not associated with a spike in deaths.

because of the vaccine. So this is really clear evidence that the vaccine works.

Speaker 4 And all this information was available to Asima Hotra at the time of this conversation.

Speaker 2 He mentions that

Speaker 2 initially people thought they had a 50-50 chance of getting that disease. And then they found out that it was one in 100.

Speaker 2

And I feel like, you know, we definitely had other things in place in the United States to make sure that you would have less of a chance to get it. We did lockdowns.

People worked from home.

Speaker 2 Tons of businesses sent people home where they started working from home. Lots of people lost their jobs because of it and they didn't want to wind up going to work.

Speaker 2 We suddenly had all this influx of people, like especially grocery stores, allowed people to order online and then you could pick up the groceries instead of going into the store.

Speaker 2

There's all these other things. People started shopping online more.

You know, people were self-quarantining.

Speaker 2 Even after the vaccine was available, even after they were vaccinated, they still stayed out of the public, didn't go out to restaurants, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Speaker 2 So this number that he quotes, this one in 100 number.

Speaker 2 It wasn't like people immediately like went back out into the world. There was a slow trickle of people who started to reintroduce themselves back into the world.

Speaker 2 So for him to use this number and to say, well, well, there's a one in 100 chance, it's like, yeah, well, a lot of people were being cautious.

Speaker 2 And so you can't, we can't look at that number to say, well, what would have happened if everybody just went balls to the wall and said, screw it?

Speaker 2 What if we were all just like Florida or whatever and just said, hey, well, everything's open and nobody cares and we're not going to do any kind of measures. How many people would have got it then?

Speaker 2 And so he's not looking at it in that sense. And I think that why he's trying to frame it like this is to show Joe that it wasn't a big deal.

Speaker 2 It's not a big deal and we shouldn't have treated it like a big deal. And I think that that is really damaging, bad misinformation from someone who is a medical doctor.

Speaker 4 Exactly. Like I said, it killed one in 300 of the UK people.

Speaker 4 It's a lot of people, man.

Speaker 2

It's a lot of people. All right.

So now they're going to talk about why, sort of the psychological manipulation of the whole thing.

Speaker 5 The vaccine. Does that make sense?

Speaker 6 It does make sense. And then also there's this false narrative that was repeated continuously, continuously during the beginning, which was this was going to stop the infection.

Speaker 6