Chris Voss Says Trump's Secret Weapon Is Empathy

Press play and read along

Transcript

Speaker 1

This podcast is supported by AT ⁇ T, the network that helps Americans make connections. When you compare, there is no comparison.

AT ⁇ T.

Speaker 2

Hi, everyone. If you're listening to the interview, I'm assuming you are a fan of podcasts.

So I want to tell you about a new listening experience in the New York Times app.

Speaker 2 If you already have the app, check out the listen tab at the bottom of the screen. And if you don't have the app, what are you waiting for? I love the listen tab.

Speaker 2

I love that I can swipe through clips from different podcasts. It makes it so easy to find something to start listening to.

And the listen tab has more than just podcasts.

Speaker 2 It's also got narrated articles from the Times that you can listen to while you're commuting or running errands or folding the laundry.

Speaker 2 Really great for actually getting to those longer articles you've been meaning to read. And of course, the New York Times app is great for more than just audio.

Speaker 2 The app makes it easy to stay caught up throughout the day with breaking news alerts and live blogs.

Speaker 2 And I love the lifestyle section, which is this beautifully visual, scrollable feed of our best arts, culture, and lifestyle stories.

Speaker 2 So go to the App Store, get the New York Times app, and tap listen at the bottom of the screen to start exploring. Okay, now on to today's episode.

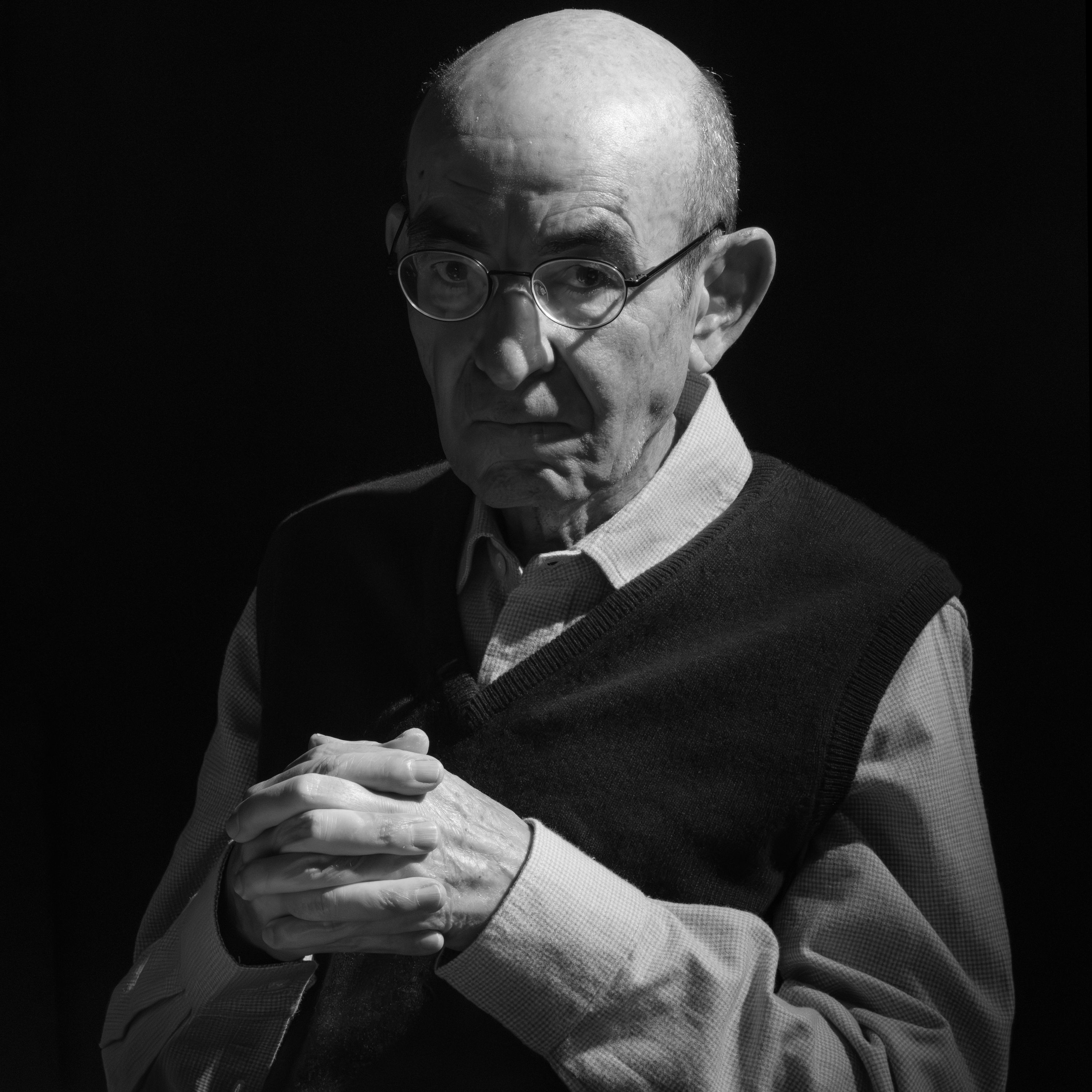

Speaker 3 From the New York Times, this is the interview. I'm David Marchese.

Speaker 3 Whether it's tariffs, domestic politics, or global conflicts, President Trump likes to boast about his dealmaking.

Speaker 3 The way he conducts his negotiations so publicly on social media has made it feel almost mandatory to have an opinion about how he does it.

Speaker 3 But what does an actual negotiation expert think of the so-called deal maker-in-chief?

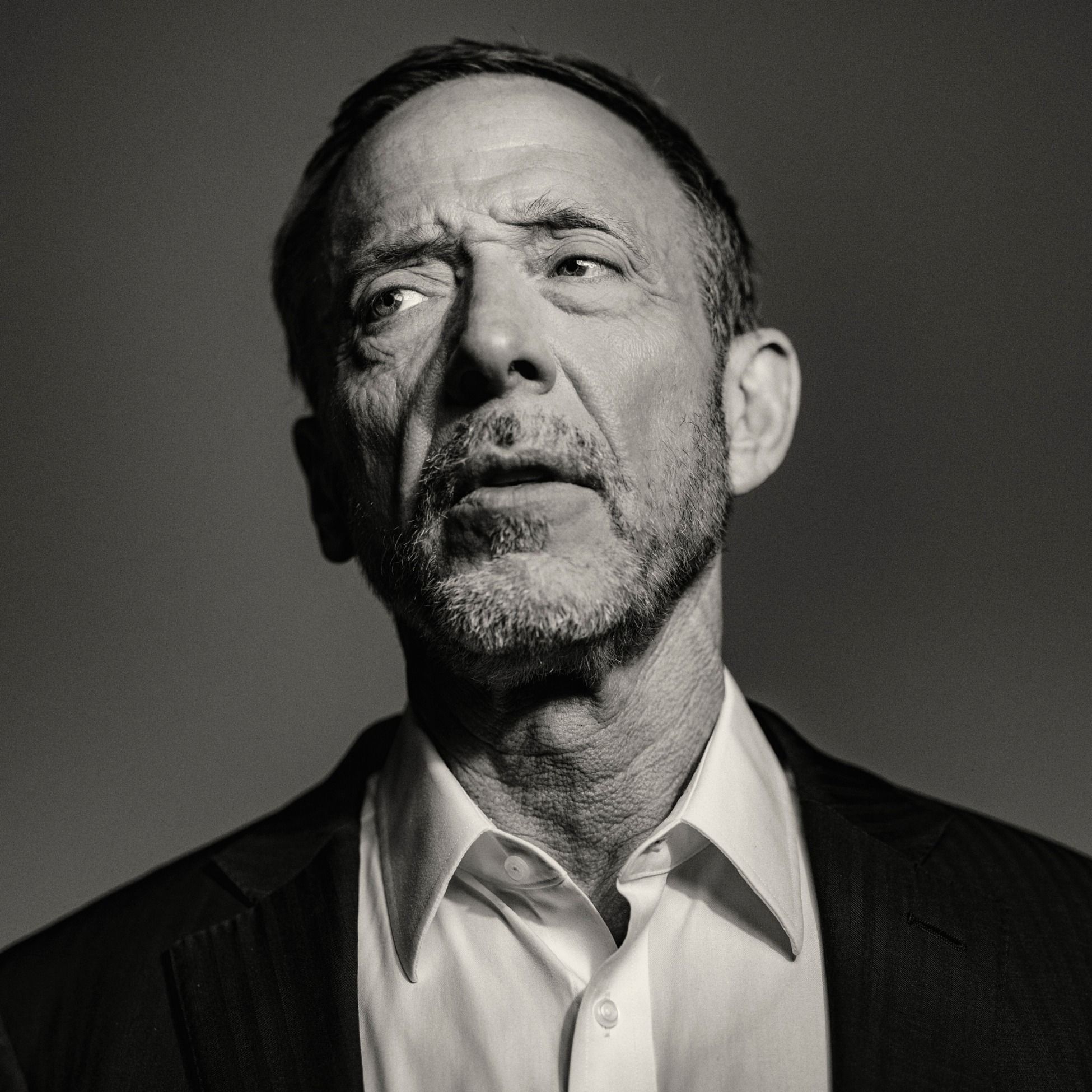

Speaker 3 Chris Voss was at the FBI for nearly 25 years, where he eventually became their lead international kidnapping negotiator. He worked on over 150 hostage negotiations.

Speaker 3 Now he's a hugely influential public speaker, private coach, and the CEO of the Black Swan Group, a company that teaches negotiation around the world.

Speaker 3 His book on negotiation strategies, Never Split the Difference, has been a perennial bestseller since it was published in 2016, with millions of copies sold in this country alone.

Speaker 3 Voss recommends a host of techniques to help us get what we want from our bosses, our relationship partners, and even it's fair to say life in general.

Speaker 3 Things like mirroring the other person conversationally, understanding the personality type across the table from you, and even putting on what he calls late-night FM DJ voice to help dial down the tension.

Speaker 3 I spoke with Foss about Trump's skills, his own past high-stakes negotiations, and the benefit of approaching life as a deal waiting to be made.

Speaker 3 Here's my conversation with Chris Foss.

Speaker 3

Hi, Chris. How are you? Hi, David.

Good to see you. I'm good.

How about you? I'm good. I'm good.

So I'm here at the Times offices in New York, and you're in Las Vegas. Is that right?

Speaker 3

That's what they tell me. Yeah.

Yeah. Do you gamble?

Speaker 3 Not in that literal sense. You know, life is my game, if you will.

Speaker 3 I have so many questions for you, but the first one is, how do you wind up becoming a hostage negotiator? Yeah, well, you start in a small town in Iowa.

Speaker 3 You go up to I-80 and you you make a right

Speaker 3

and you end up in New York. I always like crisis response.

I believe in decision-making. So I was originally a SWAT guy.

I was on a SWAT team in Pittsburgh and

Speaker 3 transferred to New York, tried out for the FBI's hostage rescue team, the FBI's equivalent of the Navy SEALs.

Speaker 3

I re-injured an old knee injury and realized that I want to stay in crisis response, but I was going to continue to get injured as a swatter. So we had hostage negotiators.

It looked easy.

Speaker 3 How hard could it be? I talked to people every day.

Speaker 3 And I volunteered for the negotiation team, was rejected

Speaker 3

and asked what I could do to get on. Woman that was in charge said, go volunteer on a suicide hotline.

I did and discovered the magic of emotional intelligence. And then I was hooked.

Speaker 3 Got me on the hostage negotiation team. And, you know, my career just, I sort of never looked back after that.

Speaker 3 Is there a story that stands out from early in your career as a hostage negotiator or a situation that really taught you something?

Speaker 3 Yeah, well,

Speaker 3

you know, a couple stories from early on a suicide hotline, a variety of stories there. But I negotiated the Chase Manhattan Bank Robbery.

And bank robberies with hostages are really rare events.

Speaker 3 When was this, roughly? 93.

Speaker 3 And previous one significant event, bank robbery with hostages, was Dog Day Afternoon.

Speaker 3 So the lead bank robber at the Chase Bank said, the guys I'm with are so dangerous, I'm scared of them. If they catch me on the phone with you guys, I don't know what they're going.

Speaker 3 Oh, here they come. I got to get off the phone.

Speaker 3

And he was doing his best to diminish his influence and his ability. behind the scenes because he's calling all the shots.

Like he was putting up a smokescreen. He was calm.

Speaker 3 He was in control of his own emotions the entire time. And I look back on that.

Speaker 3 This guy, bad guy in the bank actually displayed the characteristics of a great CEO negotiator.

Speaker 3 Great CEO at the negotiation table is going to say, look, man, I got all these people I'm accountable to.

Speaker 3 You know, if I make the wrong decision here, my board's going to fire me. I just, I'm scared to death of my board.

Speaker 3

I'm like, you know, you got to watch out for the guy who's diminishing his authority at the table. That's an influential dude.

And And that was exactly what this guy was doing.

Speaker 3 When did you really start to understand that certain principles that you were learning in hostage negotiation could also work effectively in non-life and death situations, like in business or just in life?

Speaker 3

Yeah, it was really on the crisis hotline. Suicide hotline is just the application of emotional intelligence.

You know, the magic of empathy not being sympathy,

Speaker 3 not being compassion even, but being a precursor to compassion. And you start applying empathy in that form to all problems and they solve real fast.

Speaker 3 And so I just remember thinking, you know, this empathy, it's a very caring thing to do.

Speaker 3 Shouldn't I be able to do that with people that matter to me? I mean, why has it got to be restricted to somebody who's in crisis?

Speaker 3 I started to experiment with it in my personal life, in my professional life.

Speaker 3 And every now and then I'd hit a home run that I didn't expect.

Speaker 3 At one point in time, I remember being in a conversation with a person and she said to me, you're reading my mind.

Speaker 3 And I'm like, no, I'm reading your emotions. It feels like I'm reading your mind.

Speaker 3 And then I began to

Speaker 3

really understand the different levels of it. Like hostage negotiators across the U.S.

will tell you, yeah, it works with bad guys, but it doesn't work at home.

Speaker 3

And I wasn't willing to accept that premise. Aaron Powell, Your approach is rooted in the term you use as tactical empathy.

Can you explain what that is and why it's effective in negotiation?

Speaker 3 Yeah, the real roots are in Carl Rogers, American psychologist, 50s, 60s, 70s.

Speaker 3 He wrote in his book, when someone feels thoroughly understood, you release potent forces for change within them.

Speaker 3 Not agreed with, but understood.

Speaker 3 Now, in the last few years with neuroscience, the potent forces for change are actually the triggering of neurochemicals in you, oxytocin, serotonin, when you feel thoroughly hurt.

Speaker 3 So you're less adversarial.

Speaker 3 And then the demonstration of understanding, articulation of the other side's point of view.

Speaker 3 And purely that, no agreement at all. Just, and you can even say, this is how you feel.

Speaker 3

Before I disagree with you, this is how you feel. That's the application of empathy.

I think I veered away from your question a little bit. No, no, I was just asking what tactical empathy is.

Speaker 3

So tactical. And how it's effective, yeah.

How'd the word tactical get put in front of it? Because you want to appeal to men, probably.

Speaker 3 Look at them tactical.

Speaker 3 Yeah, that's exactly it.

Speaker 3

That's exactly it. Empathy is thought of as this, oh, I feel bad for you.

Oh, I'm on your side. You know, this soft, spongy thing.

Speaker 3 Way back when Hillary runs for president, she says, you know, I'm going to use empathy in international negotiations, and she gets barbecued for it as if it's weakness. It's not.

Speaker 3

So we threw the word tactical in front of it, you know, the same way you can't teach a Navy SEAL yoga breathing. You got to tell them it's tactical breathing.

And then they go, oh, okay, I'll do that.

Speaker 3 Can you maybe give me an example of something that shows how tactical empathy is effective in a negotiation in a way that power or pure rational thinking or force of argument is not?

Speaker 3 Yeah, a couple of examples, if I can. So I used to use it all the time when I was in New York warking terrorism.

Speaker 3 You know, we had a major case, early 90s, against a blind sheikh, a legitimate Muslim cleric who also committed a lot of crimes.

Speaker 3 So we got to talk to Middle Eastern Muslims, principally Muslims that are mostly Egyptian, Sudanese, mostly, you know, his community was mostly Egyptian.

Speaker 3 So I'd sit down with them. They got their guard up.

Speaker 3 And I go, you believe that for the last 200 years, there's been a a succession of American governments that have been anti-Islamic. And they'd be like, yeah,

Speaker 3

yeah, that's right. And then they'd be open to collaborating.

So that's me trying to capture their perspective. Now,

Speaker 3 similar example, somebody I'm coaching during the pandemic, landlords raising a rent.

Speaker 3 From a tenant's point of view, especially if you're a good tenant, it makes no sense to raise my rent when I'm having trouble making a living. The world is shut down economically.

Speaker 3 We're all struggling. You want to raise my rent?

Speaker 3 The tenant approaches the landlord and says, you know, you want to raise the rent because your bills aren't going down.

Speaker 3 Your taxes aren't going down.

Speaker 3

You got monthly utility payments to make. Your grocery prices are going up.

These are the reasons you want to raise the rent.

Speaker 3 And the landlord says, that's right.

Speaker 3 But if keeping you as a tenant, a good tenant is what I got to do by not raising a rent, I'm not going to raise the rent.

Speaker 3 So what happens when you fully articulate the other side's point of view?

Speaker 3 So much defensiveness is deactivated

Speaker 3 that at a bare minimum, they're going to move closer to your position.

Speaker 3 And then if you have a real negotiation, now you're getting down to what people really need to deal with.

Speaker 3 Because a lot of it is how much do they need to simply be heard and respected and understood before they make the deal. deal?

Speaker 3 How much does it matter if the person across the negotiating table has empathy for you?

Speaker 3 What if, you know, they're disrespectful to me or dismissive of me or just sort of don't care about where I'm coming from? Is that an insurmountable roadblock? No, it's not.

Speaker 3 First of all, let's talk about empathy as a skill, not something

Speaker 3 an emotional characteristic. If you start there, then it frees you up to use it as a skill with anybody on earth.

Speaker 3 Because the act of trying to

Speaker 3

even articulate how the other side is feeling calms you down. It kicks in a certain amount of reason in you.

It broadens your perspective. Now, the percentage of people that will never go there.

Speaker 3 I need to know if you fall into what I refer to as the 7%ers.

Speaker 3 Hostage negotiators are successful roughly 93% of the time.

Speaker 3 You got to accept the fact that 7% of the time, you're never going to make a deal with the other person.

Speaker 3 You got to smoke that out early. What are the indicators? Yeah, what are they? The first one is if I apply empathy to you,

Speaker 3 your reaction to that tells me who you are.

Speaker 3 If I am determined to show you that I want to be as collaborative with you as possible and you reject me at every step,

Speaker 3 You fall possibly within a 7%er. Now, I need to know, are you rejecting me because you're predatory

Speaker 3 or because you're overwhelmed by your own pressure?

Speaker 3 But I'm now in one of those two categories because this diagnostic tells me how we're going to proceed. Right.

Speaker 3 If you're only under pressure and you can feel no empathy for me because of the massive amount of pressure you're under, if I can find a way to deactivate some of that pressure, I'm going to find out whether or not we can collaborate.

Speaker 3 Case in point,

Speaker 3 company in the Middle East that were coaching their executives, counterpart in South Africa, they've already referred to as the bully, shouts at these guys constantly.

Speaker 3 They're in the midst of the negotiation, and what he's demanding violates the agreement. They got a lawyer at the table, count on the lawyer to inflame the situation.

Speaker 3 The lawyer looks at him and says, do you want me to read the terms of the agreement to you right now?

Speaker 3 That's going to do nothing but make him angry.

Speaker 3

And he starts screaming at the guy. He He says, I don't care what the terms of the agreement say.

I don't care what you do. I don't care what you say to me.

Speaker 3 So fortunately, they're calm enough in the moment. The other executive, using his late-night FM DJ voice.

Speaker 3

Which you do very effectively. All right.

It's clear. Yeah.

He says, Yes, you do.

Speaker 3 Nice.

Speaker 3 He says to him,

Speaker 3 how about if we just take a break?

Speaker 3

So they're like, all right. They get up.

They take five.

Speaker 3 He passes the executive in the hall,

Speaker 3 and he says, seems like you're under a lot of pressure. And the guy goes, oh, God, you have no idea.

Speaker 3 You guys' project is the only one that's working for me. I'm getting killed on all these other projects, and I'm worried about losing my job.

Speaker 3 And I realized it was inappropriate for me to take it out on you guys.

Speaker 3

He's attacking. He sounded like he was a 7%er.

He sounded predatory. They said he was a bully.

Speaker 3 But as soon as they found out he he was under pressure and he was grateful that they recognized that, they ended up working things out.

Speaker 3 I want to stick with the idea of empathy for a bit. I don't know if you saw, but there was this quote going around earlier.

Speaker 3

You know, Elon Musk said that empathy is a fundamental weakness of Western civilization. I think he called it a bug that can be manipulated.

Do you give any credence to that kind of thinking?

Speaker 3 Well, you know, there's a lot of interesting stuff in there. The first thing is, what's your definition of empathy?

Speaker 3 And if it's being able to articulate the other side's point of view without agreeing with it or disagreeing with it,

Speaker 3 it's not a weakness. It's a highly evolved application of emotional intelligence analysis.

Speaker 3 That's one side. I think that's a little bit, if you're describing it as a weakness, a bug, Maybe as Elon was talking about it, in that definition, we differ.

Speaker 3 Now, the flip side, is it manipulation?

Speaker 3 The answer is it's an incredibly influential set of emotional intelligence skills.

Speaker 3

Similar to a knife, in one person's hand, it's a murder weapon. In another person's hand, it's a scalpel and it saves a life.

So it's an incredibly powerful tool that relies upon the user.

Speaker 3

Right. So on its own, it's value neutral, basically.

Exactly. That's right.

Speaker 3

Say, look at you. Look at you.

Got that trite out of me.

Speaker 3 I think it's somewhere near the beginning of your book, Never Split the Difference. You write about how life in so many waves revolves around negotiation.

Speaker 3 And I think that really in the last 10 years or so, the idea that negotiation is pervasive has been really amplified. And I think that's due to one person in particular, President Trump.

Speaker 3 And I think it has to do with the way he's publicly engaging in negotiation constantly. He's using this giant megaphone of social media.

Speaker 3 And I feel like President Trump's strategies look like they're all about threats and asserting leverage and trying to limit the other side's choices.

Speaker 3 But when you see Trump negotiating, what's your assessment?

Speaker 3 You know, it's really hard to get a solid gauge on him either through

Speaker 3 a social media post is limited and lacks context and what points he's trying to make and then the media's interpretation of what he said.

Speaker 3 Everybody in the media either loves him or hates him, which then means the interpretation is going to be skewed.

Speaker 3 What I'm struck by is

Speaker 3 really the reaction of people that talk to him in person and the outcomes. You know,

Speaker 3 Prime Minister Cannab Trudeau, him and Trump are throwing rocks at each other for years.

Speaker 3

Trudeau goes down to Mar-a-Largo. They meet in person.

Suddenly, they got a deal.

Speaker 3 Zelensky, leader of Ukraine, a rock fight that emerges in the Oval Office.

Speaker 3 They're talking to each other at the Pope's funeral. They got a deal.

Speaker 3 So he appears very publicly to be a blunt object.

Speaker 3 And then in person, he seems to make deals. So what's going on when he meets in person? Is he charming?

Speaker 3 So I think there's emotional intelligence skills there that don't translate through the media, which he appears to have a gun instinct for and a knack for.

Speaker 3 I think when people sit down with him in person, he seems to make deals.

Speaker 3 I would say I think it's probably

Speaker 3 oversimplification to say that Trudeau and Trump sat down and made a deal.

Speaker 3 But what effect does the perceptions that someone might have about the person with whom they're negotiating matter in the negotiation.

Speaker 3 You know, the example that comes to mind is it seems like this term taco, Trump always chickens out, seems to get under his skin.

Speaker 3 So if someone has an awareness that he's bothered by a perception that he chickens out, and also he knows that there's a perception that maybe he chickens out, Will that have an effect on the negotiations?

Speaker 3

Well, yeah. First of all, why are people using that term? Because they know it's getting under his skin.

Right. So they're not on his side.

Speaker 3 And generally speaking, you know, most negotiators, most executives who have been around for a while, they, you know, they start to pick up self-awareness,

Speaker 3 and he seems to be very aware of those sorts of things.

Speaker 3 You know, he, for lack of a better term, he throws a lot of data out there,

Speaker 3

and then he assesses the data. He throws stuff out on social media.

It's a search for data. He's provoking responses.

He's mapping the territory.

Speaker 3 He's getting as much data back as he possibly can so he can guide himself.

Speaker 3

So if you hit somebody two or three times or something gets under your skin, eventually they're going to go like, all right, you're trying that on me again. Okay, used to work.

Sorry, not anymore.

Speaker 3 You taught me a lesson. I learned it.

Speaker 3 Do you think he's a good negotiator?

Speaker 3 You know him a little, right?

Speaker 3 In passing, you know, a long time ago, we actually shared some common roots a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. What common roots?

Speaker 3 The crisis hotline I volunteered on was his family's church. I became very good friends with the minister, Arthur Caliandre, a great human being.

Speaker 3 Arthur was friends with President Trump.

Speaker 3 So

Speaker 3 I asked Arthur to ask President Trump if we could use his apartment at Trump Tower for a fundraiser for the crisis hotline.

Speaker 3 And they graciously let us use the apartment. And he graciously showed up and hosted and was an amazing host.

Speaker 3 It's the only time I've ever been in person with him at the same place. He was a phenomenal host.

Speaker 3

So he was generous at the time. He didn't have to give us the apartment and he didn't have to show up.

So

Speaker 3 that was sort of my awareness of him. So your original question is, is he good as a negotiator? Yeah.

Speaker 3 Like, I am blown away at the magic he's working in the Middle East.

Speaker 3 Like going out there and taking chances that no other American president would have ever stepped into.

Speaker 3 Starting with the Abraham Accords that were done under his guidance in his first term.

Speaker 3 Then he turns around, he recognizes the president of Syria, calls for sanctions to be removed.

Speaker 3 He's operating extremely effectively in the Middle East in a way that no other president has.

Speaker 3 And most of my global attention, not all of it, but most of it has been focused on the Middle East because of my terrorism days. You know, I got a lot of friends, mostly Sunni.

Speaker 3 Which say because of your anti-terrorism days. Yeah, there you go, right? Yeah, it was a terrorist.

Speaker 3

One man's terrorist, another man's freedom fighter. Let's be clear.

Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 3 Anyway,

Speaker 3 I'm blown away by what he's doing in the Middle East.

Speaker 3 Do you think the Trump administration demonstrates empathy?

Speaker 3 Yeah, I think he has a highly evolved understanding of how other people see things.

Speaker 3 Tell me more about that. What makes you say that?

Speaker 3 Well,

Speaker 3 the thing with Iran recently, when we decided to weigh in and add to the ordinance being dropped on the nuclear sites,

Speaker 3 you know, the reporting was,

Speaker 3 and it's hard to tell if this is accurate,

Speaker 3 the reporting was Israel was thinking about trying to take out the Iranian leader. And that Trump was against that.

Speaker 3 Now, my view for that is that's smart in a a number of reasons. First of all, if you agree to take out the head of a country,

Speaker 3 you declare there's open season and fair is fair, which means they're free to come after you.

Speaker 3

To me, there's a sense of empathy there. Not necessarily agreeing, not being on their side.

But if empathy is understanding how somebody sees it, I think he has a highly evolved sense of it.

Speaker 3 Do you think he has a highly evolved sense of empathy when it comes to understanding how other people see it on immigration?

Speaker 3

Yeah, and then I think he's making a calculation based on what he needs to move forward. I don't think he's oblivious to how people see things.

And to lack empathy is to be oblivious.

Speaker 3 Now, what decisions that causes you to make is a whole separate issue.

Speaker 3 And

Speaker 3

you're probably going to think I'm a jerk for asking this. Here we go.

Stop black swanning me. How dare you, voss me?

Speaker 3 How dare you?

Speaker 3 I just need to stick with the question of empathy and Trump and immigration just a little bit more.

Speaker 3 You're talking about it in this context of you can have an empathic understanding of the situation, but you got to make tough decisions. Help me understand

Speaker 3

how the way ICE functions is the result of remotely empathetic understanding of other people. Yeah, I don't know.

I'm not on the ground with those guys.

Speaker 3 I don't know what kind of orders are are being given.

Speaker 3 Do you want a system where the guy who's in charge tells you to do one thing and you say, no, I'm not doing it? Then the system breaks down.

Speaker 3 Well, if you think the thing is wrong, you probably should say, I'm not doing it, right?

Speaker 3

You know, there's really tough questions about that as an individual. Yeah.

And, you know, I'm seeing it from a distance. I'm not in a position to be able to offer an informed opinion on it.

Speaker 3 And yeah, I'm dodging your question.

Speaker 3

Fair enough. You know, I'm sure you must work with people all the time who come to you and they're kind of afraid of negotiation.

Yeah.

Speaker 3 You know, my hunch is that a lot of fear of negotiation is probably related to a flat-out fear of conflict.

Speaker 3

Yeah, I think I, in really broad, general terms, two out of three people are afraid of conflict. One of them loves it.

I hate those people. But yeah, they're tough, right?

Speaker 3

You know, they're hard to deal with. They beat you up, you know, they call you names and then they say, Let's go have a drink.

And you're like, what? You just call me names.

Speaker 3 You want to go have a drink with me? You got to be kidding me.

Speaker 3 Yeah, so

Speaker 3

most people don't like conflict. Some people are afraid of it.

Some people just see it as being very inefficient and avoid it because it's just inefficient. It's a waste of time.

Speaker 3 Or they're combative and they love it.

Speaker 3 So as soon as they begin to see that

Speaker 3 we can engage in negotiations and it's not a conflict, we can make it be collaborative

Speaker 3 and it'll be pretty cool. It'll actually be fun.

Speaker 3 And I'm going to brag,

Speaker 3 but there's a point to it.

Speaker 3

The book globally is 5 million copies. Sells well in every country that it's in.

Pick a country. What that tells me is

Speaker 3

people don't really want to fight. They would prefer to collaborate.

They're just not sure exactly how to get there.

Speaker 3

And the book is kind of a step-by-step guide in real clear, concise terms to how to get collaboration started. As an aside, if you will.

I can't explain why.

Speaker 3

We've seen women pick this style of negotiation up faster than men. Now, that doesn't mean they're any better at the higher end.

The top end,

Speaker 3 we're gender agnostic.

Speaker 3 But we started to see indicators of women picking up a little quicker than men.

Speaker 3 Let me change subjects for a second. You know, this, one of my best friends, the the first guy who mentioned your book to me,

Speaker 3 he runs his own company in Toronto. And he said that

Speaker 3 he said he can tell when he's in negotiation with someone who has also read Never Split the Difference.

Speaker 3 What advice do you have for someone who's entered into a negotiation and understands that both sides are playing the same game? Yeah, okay. I love that question.

Speaker 3

So first of all, it's not if it's going to happen, it's when. You know, the book sold 4 million copies, domestic U.S.

Okay, okay. You're going to encounter it.

Speaker 3 So my gut instinct right away is, what's it being used for? Are you trying to collaborate with me? Are you trying to cheat me? I'm going to be able to smell your intent early on.

Speaker 3 Are you using the skills to collaborate with me to demonstrate understanding to get to an outcome? I got no problem with that. We do that with each other all the time.

Speaker 3 Everybody on my team uses this stuff on me. I encourage them to do so.

Speaker 3 Somebody starts out in

Speaker 3 five minutes, 15 minutes in, I know they're using the skills against me.

Speaker 3

Okay, now I know who you are. So, again, it's a power-neutral thing.

And if you're willing to listen, if you're willing to accept the fact that you don't want to make a deal with everybody,

Speaker 3 then, yeah, I got no problem with you using the skills.

Speaker 3 How many books did I sell again? Could you remind me?

Speaker 3 Chris, just before we go, I have my mid-year performance evaluation next week.

Speaker 3 There's something I want.

Speaker 3 I shouldn't say what it is. What's the number one thing I should be thinking about when I go into that evaluation?

Speaker 3 They see you as selfish

Speaker 3 because they know you're going to come in there with an ask.

Speaker 3 Everybody that walks in wants to get paid more for the same amount of work.

Speaker 3 Now, that might not be what's actually happening,

Speaker 3 but empathy is understanding how the other side sees things. So you're starting by saying like, look, I know I'm just another selfish employee that just wants more for the same amount of work.

Speaker 3 Now, collaboratively with your boss, it's not so much where we've been, but where we're going.

Speaker 3 Now you start talking to me about where we're going, about how you're going to make my life better.

Speaker 3 And I got a lot more latitude on what I could pay you or what I could let you do.

Speaker 3 Start thinking about how your boss evaluates you and then contribute to that collaboratively. Now not only is it likely more valuable, but you're also saving your boss some thinking.

Speaker 3 You ain't asking him to figure out how you pay you more.

Speaker 3 You're saying, here's how you can pay me more.

Speaker 3 Enable him to do it for you.

Speaker 3 And when you start looking at it like that, then it becomes a completely different conversation.

Speaker 3 You know, when we talk again, I'm going to need way more time than we initially agreed on.

Speaker 3 You know, never be so sure of what you want that you wouldn't take something better.

Speaker 3 Thank you very much for taking the time today, and I'll talk to you again in a little bit. I look forward to it.

Speaker 3 After the break, Chris and I speak again about a painful negotiation from his personal life. I told my son just a couple years ago, there's no question I could have been a better man.

Speaker 3 Simultaneously, that doesn't mean it would have changed things.

Speaker 1 This podcast is supported by the American Petroleum Institute. Energy demand is rising, and the infrastructure we build today will power generations to come.

Speaker 1 We can deliver affordable, reliable, and innovative energy solutions for all Americans, but we need to overhaul our broken permitting process to make that happen.

Speaker 1 It's time to modernize and build, because when America builds, America wins. Read our plan to secure America's future at permittingreformnow.org.

Speaker 4 This podcast is supported by The Nightly, a podcast from Hatch.

Speaker 4 For your commute, you catch up on the day's current events. But on your way to bed, it's time to unwind with The Nightly.

Speaker 4 The award-winning podcast designed exclusively for sleep from the sleep experts at Hatch.

Speaker 4 The Nightly is a late-night chat with your funniest friends where pop culture news pairs best with a well-earned snooze. Add some fun to your bedtime routine seven nights a week.

Speaker 4 Find the nightly wherever you listen to podcasts and fall asleep smiling.

Speaker 5

We all have moments when we could have done better. Like cutting your own hair.

Yikes. Or forgetting sunscreen so now you look like a tomato.

Ouch. Could have done better.

Speaker 5

Same goes for where you invest. Level up and invest smarter with Schwab.

Get market insights, education, and human help when you need it. Learn more at schwab.com.

Speaker 3

Hi, Chris. How are you? I'm good, David.

Good to be here with you again today.

Speaker 3 I was thinking that in our conversation so far, we talked a lot about your ideas, about your work, but I thought I still don't feel like I have a firm handle on you, on who Chris Voss is.

Speaker 3 Hold on, hold on. Are you going to make me cry? I hope so.

Speaker 3 Do you want to cry? I'm a very emotional guy, you know.

Speaker 3 I probably, I probably don't look that way, but you know, deep down inside, soft gooey inside, right? Let's see if we can get to that deep down inside.

Speaker 3 You know,

Speaker 3 I feel like in a sort of ambient way, my sense of people who

Speaker 3 are really focused on ideas about how to effectively manage interpersonal communication or who develop systems for getting along with other people, those interests don't develop in a vacuum.

Speaker 3 My hunch is that they maybe have something to do with the desire for control. Does that ring true for you?

Speaker 3

I'm not sure control. You know, I like solutions.

I like figuring things out. I suppose I would have been attracted to the idea of control in my younger days.

Speaker 3 Why is that? Well,

Speaker 3 the first time I came across a phrase in a negotiation, the secret to gaining the upper hand in a negotiation is giving the other side the illusion of control. I went like, oh, all right.

Speaker 3 So that resonates with me. And I think that me being an assertive, I think assertives like to have control.

Speaker 3

They want to steer things. And so that may be a vulnerability of mine of wanting control, possibly.

So yeah, that there could be some intertwining of concepts there.

Speaker 3 What's a negotiation that you lost in your life that stands out?

Speaker 3

Not in your work, just in your personal life. In my life.

Yeah.

Speaker 3 You know, one of the biggest ones I probably lost overall was getting divorced. And I remember I told my son just a couple of years ago, there's no question I could have been a better man.

Speaker 3 Simultaneously, that doesn't mean it would have changed things.

Speaker 3 And as we look back over our lives, I mean, I think that's a critical issue. Could I have done it better and would it have changed the outcome? Those aren't the same things.

Speaker 3 So I suppose probably the negotiation overall for my marriage, I was unaware of the impact of being direct and honest and harsh and could have been a far better human being, far better man.

Speaker 3 Would that have changed things? I don't know that it would have changed it.

Speaker 3 You know, you brought up this 7%

Speaker 3 number when we were talking before in the context of hostage negotiators. They're successful roughly 93% of the time, unsuccessful roughly 7% of the time.

Speaker 3 Yeah. When were you part of the 7%?

Speaker 3 Oh, wow.

Speaker 3 The first time things went really bad was in the second case who worked in the Philippines, the Burnham-Sibero case. Sorry, can you say that name again? What was it? Martin Burnham.

Speaker 3

Guillermo Sibero was murdered by Abu Saef. A lot of Filipinos died.

Two out of three of the Americans that were taken were ultimately killed.

Speaker 3 You know, that was a big wake-up call to get better and that, yeah, sometimes it's not going to work out.

Speaker 3

So that was the first one. Then there was a string of kidnappings al-Qaeda did 2004 timeframe.

They were killing everybody they get their hands on to make a point.

Speaker 3

And they wanted to make it look like that they were negotiating when they weren't. It was kidnapping for murder.

Where was this? Where did this go?

Speaker 3 You know, there was several in Iraq. There was one in Saudi Arabia, the Paul Johnson case case in Saudi Arabia.

Speaker 3 But, you know, they planned on making a point by murdering him on deadline, which is what they did.

Speaker 3 So when you're working on a negotiation and a hostage gets killed, how do you move on from that? It seems to me there would be a pretty strong impulse to walk away from the work.

Speaker 3 There is.

Speaker 3 And that's the critical issue between the people that want to hang in there and get better and those that are defeated by failure. A lot of people are defeated by failure.

Speaker 3 Understandably in that instance. Understandably.

Speaker 3 I never blamed anybody that was involved to want to bow out and go do something else where the chance of somebody getting killed while you were working was there.

Speaker 3 When Mark Burnham was killed, and that was the first hostage that I ever lost, I thought that was the worst moment of my life

Speaker 3 until I remember sitting in the audience on another hostage negotiator's presentation probably about four years later. And he talked about the trauma of this infant getting killed.

Speaker 3 And he said, you know, I don't know why I keep talking about this, giving a presentation. And he said, because it's something bad that happened to me on a winter's day.

Speaker 3 And I remember thinking at the time, happened to you.

Speaker 3 That wasn't your child.

Speaker 3 That wasn't your brother. That wasn't your son.

Speaker 3

And then I remember thinking, like, this is exactly as self-centered as I've been. It hurt me.

It wasn't a blood relative. I didn't lose a member of my family.

Speaker 3

So at that time, I remember thinking like, all right, so yeah, it was bad for you. It was worse for others.

Stop feeling sorry for yourself.

Speaker 3 I just want to sort of

Speaker 3 take things in a slightly different direction for a minute. But

Speaker 3 in Never Split the Difference, you're somewhat critical of the idea of compromise.

Speaker 3

Somewhat. I'm being friendly.

You're being kind.

Speaker 3 And from where I'm sitting, I mean, what do I know about anything? But I think, oh, gosh, this seems like

Speaker 3 things might be going a lot more smoothly if more people were more comfortable with the idea of compromise. So what's wrong with compromise?

Speaker 3 Well, compromise is guaranteed lose-lose.

Speaker 3 There's no way around that.

Speaker 3 And so I don't like a strategy where lose-lose. That's not just a matter of perspective, though.

Speaker 3 I hate to interrupt, but like, why couldn't a lose-lose in a compromise situation just as easily be understood as a win-win?

Speaker 3

Wow. Okay.

Why couldn't it just as easily be understood as a win? Yeah, why is it necessarily lose-lose?

Speaker 3 Well, because I got a compromise basically is I believe I have an outcome in mind,

Speaker 3 and you believe you have an outcome in mind. We're not sure which is right, so I'm going to water down mine.

Speaker 3 You're going to water down yours, and then we're going to go, let's go with two lesser ideas.

Speaker 3 Compromises most of the time is people get lazy. It's a guarantee of mediocrity.

Speaker 3 It's, you know, being consigned to being a C student in outcome for the rest of your life. Now, I suppose that's superior to being an F student.

Speaker 3 But we were not built to be C students for the rest of our lives.

Speaker 3 A metaphor. Steel, and you metallurgists out there are going going to get mad at me over this.

Speaker 3 But steel is 2% carbon, 98% iron. That's not a compromise.

Speaker 3 That's finding out what the best combination is and

Speaker 3 producing something the world has never seen before that was far better than either one of those by themselves were. 2%, 98%.

Speaker 3 That's not 50-50. And so if you really want to improve things, you can't compromise.

Speaker 3 It seems like it would be

Speaker 3 a difficult thing mentally to always be approaching conversations and interactions from a goal-oriented standpoint is that always how you're thinking about conversations no i mean i get a rough idea where i want to go every time

Speaker 3 roughly yeah i mean everybody does you're you're human and vision drives decision nobody engages in anything without having a vision of where they think it's got to go it's how we're wired you can't get away from that

Speaker 3 so to me my real desire is to try to let go of a goal because that gives you tunnel vision,

Speaker 3 you have blinders on,

Speaker 3 and to try to discover what's really possible.

Speaker 3 I'm not always successful at it, but when I can lay back and let an outcome unfold, it comes much more easily.

Speaker 3 Do you see what we're engaged in as a negotiation? Probably. Yeah.

Speaker 3 Yeah.

Speaker 3 You know, I think we each are seeking, the objective is to uncover some kind of truth that we can share or discover a truth through the combination of this conversation.

Speaker 3 I think we're trying to uncover something that's worth people listening to and maybe taking away.

Speaker 3

and using it to make their lives better. So, yeah, it's a negotiation.

That's the outcome I think we're both after. And did you achieve it?

Speaker 3 You know, I don't know.

Speaker 3 I think there's a pretty good chance we've said something together that's going to matter to somebody. So even if we only packed one life, then it was a worthy outcome.

Speaker 3 Oh, before I let you go, one last thing. How's a kid from Iowa end up sounding like a Brooklyn cop?

Speaker 3

You know, they ask me that every time I'm in Iowa. Like, where the hell are you from? Like, you're not from here.

You don't sound like it.

Speaker 3 Then I sit down at a bar in New York and and they go, you from Wyoming? You know, it's crazy. I can't wait.

Speaker 3 That's Chris Boss.

Speaker 3 To watch this interview and many others, you can subscribe to our new YouTube channel at youtube.com slash at symbol, the interview podcast. This conversation was produced by Wyatt Orme.

Speaker 3

It was edited by Annabel Bacon. Mixing by Sonia Herrero.

Original music by Dan Powell and Marion Lozano. Video of this interview was produced by Brooke Minters and Paola Newdorf.

Speaker 3

Cinematography by Alfredo Chiarapa and Sean Gearing. Additional camera work by Ahmed Abou Shama.

Audio by Kenton Kabinsky. It was edited by Mark Zemmel.

Photography by Devin Yalkin.

Speaker 3 Our senior booker is Priya Matthew, and Seth Kelly is our senior producer. Our executive producer is Allison Benedict.

Speaker 3 Special thanks to Rory Walsh, Renan Barelli, Jeffrey Miranda, Nick Pittman, Maddie Masiello, Zach Caldwell, Jake Silverstein, Paula Schuman, and Sam Dolnick.

Speaker 3 I'm David Marchese, and this is the interview from the New York Times.

Speaker 5

We all have moments when we could have done better. Like cutting your own hair.

Yikes. Or forgetting sunscreen so now you look like a tomato.

Ouch. Could've done better.

Speaker 5

Same goes for where you invest. Level up and invest smarter with Schwab.

Get market insights, education, and human help when you need it. Learn more at schwab.com.